1841

COPYHOLD CUTTING

COPYHOLD CUTTING TRAIN CRASH

THE FIRST RECORDED ACCIDENT ON THE NEWLY

OPENED LINE

2nd OCTOBER 1841

Involving (Leading Engine)

Driver Charles Goldsmith & Fireman Robert Marshall

& (Rear Engine) Driver James Jackson & Fireman Robert Field

EXTRACTED AND ADAPTED FROM THE BOARD OF TRADE REPORTED

BY EARL OF RIPON

This disaster occurred at Copyhold cutting, where the fatal over throw occurred on the

2nd of October, which involved the 10.45 a.m. down train from London Bridge to

Brighton. The train left London Bridge with nine first class carriages, one composite

carriage and two private coaches on trucks, holding a total of 97 passengers. The

firemen of both engines were killed together with two passengers, (servants of a Doctor).

In compliance with your Lordship's request, contained in the instructions forwarded to me by Mr. Laing. I proceeded on Wednesday, the 6th instant, to Brighton, having on my way

arranged with Mr. Statham, the superintending engineer of the line, to meet him at the

Brighton station on Thursday morning, to proceed up the line by a special engine immediately after the despatch of the 10 h. 45 m. morning train.

This I did accordingly, but as your Lordship has been already informed, on our approaching the south end of Patcham Tunnel a signal was made to stop, and on inquiring the cause we were informed of the dangerous condition of the front of that structure, which was obviously in a falling state. Of course I did not proceed, but returned to Brighton with the engine, leaving Mr. Statham at the tunnel. In a short time afterwards it appears that the front and a great part of the wing walls came down.

Before I left the tunnel a person was dispatched to end of it to warn the down train not to

advance, and my arrival at the Brighton Station prevented the dispatch of the 11h. 45m. train.

The Patcham Tunnel is about two miles and a half from the Brighton terminus. Steps were immediately taken to remove the rubbish, and by the next morning the line was again opened.

This new disaster prevented my inspection of the Copyhold cutting, where the fatal over throw occurred on the second instant, till the next day. I was then supplied with a special engine and carriage and was accompanied by Mr. Rastrick, the engineer-in-chief of the line, to the Hayward Heath Station; our driver being the man Jackson, who had charge of the

second engine (Loco No.22) on the day of the accident, and whom I had thus the means

of questioning on the spot, as I had also the labourer Copley, who had made the signal

to indicate the necessity of caution the moment before the first engine was thrown off the

line. I also saw at a beer shop the guard Hitchens, who was so severely injured, but he

was too ill to be able to give me any information. I saw this man again the next day; he

then appeared better, but could give me no account; all that he knew was the accident

was momentary. The driver of the first engine (loco No. 17 was to pilot the train to

Haywards Heath), Charles Goldsmith, I only saw at the Brighton Station. Although in a

weak state he is fast recovering, but his evidence amounts to little more than that of

Hitchens. He saw the signal given by Copley, but too late to be of any service. He states

the awe d to have been, on entering the cutting about 30 miles per hour but could a sign

no caused for the accident.

On examining the place of the fatal occurrence nothing could be seen, or expected to be

seen, after the lapse of six days, to indicate its immediate cause, although there was

sufficient evidence of the extreme violence of the concussion. Four of the rails, weighing

75 lbs. per yard, or 375 lb. each, which had sustained the shock of the engine, were bent

and twisted in all directions, and one of them had on one side its flange stripped off for

about two feet of its length, as if out by the moat powerful shears; hut these rails having

been replaced by other immediately after the accident, I could form no opinion from the appearance of the mad that could lead me to any conclusion, although from other circumstances I feel not the slightest doubt on the subject.

The place where the accident occurred is near the 36½ mile post from London, within about a mile of the north end of the Hayward Heath Tunnel, which is a little below the Hayward Heath Station. The soil in this cutting, and for some distance down the line, is of a very absorbent and treacherous character, becoming in its wet state nearly semi-fluid, mud yet when dry or well drained it appears be perfectly sound; and I am bound to state that I stood at this and observed trains passing with considerable speed both up and down the line, and that their motion was exceedingly steady, that is, free from rocking, which is generally in obvious where a line is defective.

I have watched this effect, and have experimented upon it on several lines, and I am not

aware that I ever saw less oscillatory motion. But it must be observed that at this time

everything that could be done had been hone to car off the water. For a day or two before the accident the rain had been very heavy, and I have no doubt, from the nature of the soil, and the evidence of Copley, that the road was at the time in what he describes "as a light state," which he afterwards explained by saying-when there is much rain the wet pushes up the rails and makes them uneven, but that was not the case on Saturday.I asked him, "If the road was not in that date on Saturday, and the speed not greater than usual, why he gave the signal;" hut all I could learn was they had done so for two or three days.Weighing these circumstances, viz., the nature of the soil, the great quantities of rain that had fallen, the admission that a caution signal was made, and has been made for some days before, I feel no doubt whatever that the unsound bearing of some one or more of them sleepers at the time was one cause of the accident.

With respect to the speed of the engine at the time, there are considerable discrepancies in the evidence. Jackson, the driver, states that the speed did not exceed 20 or 23 miles per hour, although he admits that he has frequently passed this spot at 32 and 35 miles per hour.

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

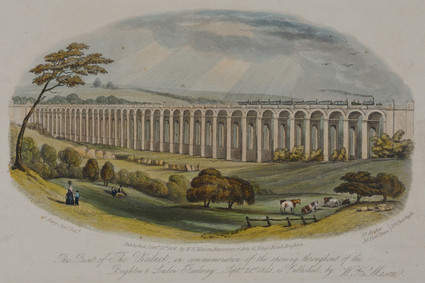

Ouse Valley Viaduct

Copley, the labourer above alluded to, says, that he observed the engine at its usual speed. Hinge, the policeman on the viaduct, says he gave the signal "stead," because he observed the train was going rather faster than usual. Now the question is, What has been the usual speed on this part of the line. The average speed on the whole line for this train is 25 miles per hour, including the time lost at four intermediate stopping places, besides the stoppage at Horley to attach the assistant engine.

This will require an average speed of at least 28 miles per hour when travelling. Now for

the first two miles after leaving Horley the line ascends 1in 460 and then for four miles

before reaching the Balcombe Tunnel it ascends 1 in 264, and thence descends for nearly

six miles to the Hayward Station at the same rate, that is 1 in 264.

From the notes and memoranda made by Sir Frederick Smith and myself in travelling

together over some thousand miles of railway, and over every variety of gradient. I have no

doubt that to preserve an average speed of 28 miles per hour though this12 miles would a

speed of 32 miles per hour on the descending side.

Now it is admitted that the train was behind its proper time, a strong reason for not going

slower than usual. Jackson denies having seen the signal “steady" on the viaduct, he seems

therefore to have had no good motive for going slower. and he states that he has frequently

passed this place at 35 miles per hour; and yet he asserts that just on this particular occasion, when such a Frightful accident occurred, he was not proceeding at more than 20 or 23 miles per hour. His statement on this head is certainly supported by the opinion of John Hardy. Eq.. M.P., who was a passenger, but it is greatly at variance with probability, and with other evidence.

It has been seen that the usual speed down this plane is about 32 miles per hour, and Hinge admitted in his evidence before the jury that he thought the speed was greater than, usual. It appears also that he made use of expressions soon after the accident, which would simply that the speed was much greater than he stated before the coroner.

Since I have been engaged on this inquiry, I have had communication with two of the

gentlemen on the jury, who met me afterwards by appointment, and whose statement throws great doubt on this man’s evidence. I quote the following from their two letters.

“I beg to state that, although on the evidence brought before them the jury would come to no other conclusion than that at which they arrived, I felt, and still feel, by no means satisfied at the statement made by John Hinge, the policeman, on the highly important point of the speed with which the train was travelling at, or immediately before. the time of the accident. I was at the Copyhold bridge about two hours after the accident happened, when this police-man addressed m e and said, that when k first saw the train coming towards him he was sure something would happen from the speed at which it was going. He said he held up his hand to signal ‘ steady.' but that his heart was up in his mouth as they passed him; that he ran to a point in the mad where he could watch them farther, and in a very short time the accident occurred. He was heard to state this by other persons also, who have, I believe, informed you of the same thing The man, however, when called as a witness denied having made any such statement. Whether he had really forgotten what he previously said, or in the excitement and alarm occasioned by the accident had stated that which was not the fact, I am unable to say; but it is obvious, that the effects on the minds of the jury would have been very different if the original account of the policeman had been substantiated before them."

The other gentleman states as follows:-" Soon after the accident occurred I went to the

spot, and accompanied one of the inspectors and a gentleman, who is a stranger to me,

to the shed where the bodies of the unfortunate victims had been deposited. A policeman

was in attendance, who volunteered the following remarks:-He said that he observed the

train approaching him near the viaduct (where he was on duty) at such a rapid rate that

he was much terrified; that he fully expected some accident to happened in consequence

of the great speed with which they were proceeding, and was only surprised it did not

occur sooner than it did; that he held up his hand as a signal to slacken speed, but that

no notice was taken of it. Being one of the jury on the inquest held two days after, I

insisted upon this man's evidence being heard. It was not until after much delay had taken place, and the coroner more than once called for him, that he made his appearance. On questioning him as to his former statement he totally denied having used such expressions as those which I had attributed to him, declared that he had not been the least frightened, nor had entertained any apprehension of fatal consequences arising from the speed, Which h he then said was not extreme; yet he allowed that he held up his hand as a caution, but could not be certain that the signal ad been seen by the driver.”

“As a juryman I did not think that I could also act as a witness; and not being aware at the

time that the policeman had made similar statements to others, who could be called upon to

give evidence of the fact, I thought I ought not to allow the policeman's previous assertions to influence the verdict, as they were not borne out by the evidence. But as it appears that

Government has commissioned you to investigate the circumstances which attended the

accident, I feel that, being no longer fettered by my position as a juryman, I should not be

acting fairly towards the public if I withheld this statement from you.”

These gentlemen, who have no wish that their names should be unnecessarily brought

before the public, are, notwithstanding, quite ready, if called upon, to substantiate what

they have thus stated.

It is not, perhaps, my place to make any comments in this report on the conduct of the

policeman; but it is impossible not to conclude from these statements, and other circumstances, that the speed down the plane was excessive, and inconsistent with the then state of the road; or, perhaps, with common prudence under any circumstances.

Of course the above statements impugn also Jackson's evidence; and I am sorry that the

jury seam to have given too much weight, in my opinion, to his explanations as to the

probable cause of the accident This man states that he has been a driver for four years and a half, three years in the service of the London and Brighton Company, before which he belonged to the London and Birmingham Company. He states that he never met with any accident himself from the four wheeled engines on the latter line; but had heard of a case of one of those engines getting off the line near Harrow.

Now surely this is very slight ground on which to come to a conclusion that such engines

are unsafe, and for attributing to the use of them two accidents on two successive days

within about a mile of each other.

It appears from a statement I have received from Mr. Bury, the maker of these engines, and who is also the superintendent of the locomotive department of the London and Birmingham Railway, that since the opening of that line, in July, 1837, they have used no other than four-wheeled engines; that they have travelled more than three million miles, which is nearly equivalent to making thirty thousand complete journeys between London and Birmingham; and that they have in no instance met with a single accident that can be said to have been occasioned be the particular construction of the engine.

There is, however, as stated by Jackson, some difference between the Birmingham and

Brighton four-wheeled engines. They have both the same stroke and the same diameter of wheels; but the former has smaller cylinders, viz., some having twelve-inch cylinders,

weighing, full of water, under 10 tons; others of thirteen-inch cylinders, weighing, under

like circumstances, between 11 and 12 tons.

On the Brighton line the four-wheeled engines have all fourteen-inch cylinders, and weigh, when charged with water and fuel, between 13 and 14 tons. This increased size of cylinder requires increased dimensions; and, the wheels being of the same diameter, necessarily raises the centre of gravity, and thus far they may be said to be more top-heavy, and are, perhaps, more liable to rock; but the difference must be very inconsiderable.

In order to form some comparison of the top-heaviness of the two engines employed on

that particular day when the accident occurred, Mr. Rastrick obligingly permitted one of

his assistants to make me two outlined elevations of them, that is, of a four-wheeled engine of precisely the same dimensions as that which was destroyed, and the other of the identical six-wheeled engine driven by Jackson. I forward with this report these two drawings, by which it will be seen, as nearly as it is possible to form an opinion, that there is little or no difference in the place of the centre of gravity in the two engines. The upper part of the boiler of the six-wheeled engine is the highest, but its water line is the lowest; as far, therefore, as relates to top heaviness on which much stress is laid by Jackson, I am of opinion there is little or no difference.

In making these remarks, I beg it may be distinctly understood that I am not advocating,

Or giving a preference to, the four-wheeled engines. My object in referring to the subject

is, that the jury, by giving too much weight to W at I consider to be an erroneous opinion, have lost sight of the main causes of the accident, which I feel the strongest conviction were over driving and a road partially injured by the heavy rains that had recently fallen. I think, moreover, that the withdrawing of those engines from the line, in compliance with the recommendation of the jury, has a tendency to give a false confidence to the Brighton passengers, while it is calculated to give unfounded alarm to those travelling on the London and Birmingham and some other lines.

It now only remains, my Lord, to inform our Lordship of the result of my examination into the circumstances attending the falling o the front of the Patcham tunnel This was, I believe, occasioned by the chalk being left at a considerable slope, which caused the "backing in," when impregnated with the excessive heavy rains, to slide along the face of the chalk, and thus by its pressure overcoming the resistance opposed to it. Mr. Rastrick also apprehends that a pipe. intended for a drain, had become by some means choaked, which increased ' the evil. A slight crack, it appears, had been observed early on the Thursday morning; but no danger was apprehended till immediately after the passage of the 10h. 45m. morning train.

In the fall of the front of the tunnel, a part of the brick work of the tunnel itself, for about

six feet, was fractured. It remained shored up the second day, hut was removed during

the following night. The remaining part is an extremely fine piece of brickwork, and is

perfectly safe, only requiring for the present a constant watching, to remove any fragments of chalk that may fall upon the line from the present nearly vertical face of the cutting. Steps will be immediately taken to reface the tunnel; and it is, I believe, Mr. Rastrick's intention to lengthen the brickwork of it a little towards Brighton.

In the further compliance with your Lordship's instructions, after making this examination I proceeded along the line with the special engine and carriage, accompanied by Mr. Rastrick, to Hayward Heath, stopping and examining everything that appeared to require it. Mr. Rastrick here left me to return to Brighton, having first appropriated m me the coupe of the carriage, in which I proceeded to Croydon ; and if I might venture to give a practical opinion relative to the construction and present state of the line, I should say that the engine has done, and well done, everything that could be effected; but he has had to deal in some parts with very treacherous materials, and time will be required for them to take up a firm and solid state.

In other parts, where the soil is better, the line is very perfect. The bridges, the viaducts,

and four out of the five tunnels, are, in regard of interior brickwork, in perfect condition;

but the Hayward Heath Tunnel is much oppressed with water from the late excessive

rains; but great efforts are being made to carry the water off, and a few days of fine

weather will enable much to be accomplished. Those parts of the line which have suffered most from the rains are two short pieces of the embankment south of the Redhill Station ; another considerable portion south of the Balcombe Tunnel, and just beyond

the Hayward Heath Tunnel southward.

Sir Frederick Smith, in his general approval of this line, has drawn the attention of the

engineer to certain portions of it, on which he conceived the safety of the public called

for specific precautions a d reduced speed. These precautions have been rendered more

particularly necessary in consequence of the recent heavy rains, which have also

produced some other weak points; and I conceive that it is most desirable that at

present, and during the approaching winter, more time should be allowed for the

journey, in order that great caution may be observed in those parts where the line has

most sufferer.

I have ascertained that both Jackson and Charles Goldsmith were discharged servants

of the London and Birmingham Company, but Goldsmith had never been a driver.

Driver Jackson had previously been employed as an engine driver since the early part of

1837, by the London & Birmingham company. After being discharged from this company in

c1838, driver Jackson later found employment with the L.B.S.C.R. having been an engine

driver for about a year and half.

LETTER from Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Frederic Smith,

covering Professor's Barlow's Report,

on the Accident on the London and Brighton Railway.

Board of Trade, October 15, 1841.

MY LORD,

Having carefully considered the accompanying report from Professor Barlow, respecting the

late fatal accident on the London and Brighton Railway, and, on the present state of the works on that line, I have the honour to acquaint your Lordship that I occur with the Professor in attributing that accident partly to the excessive speed used on the occasion in question, and partly to the defective state to which the road had been reduced by the long continuance of heavy rain; hut, believing as I do, that these two causes mainly contributed to produce this unfortunate catastrophe, yet I am most decidedly of opinion that the accident would not have happened but for the improper use of two en mes a-head on a long gradient, of rather severe inclination, falling in the direction in which the train was running.

Scarcely any practice can, in my opinion, be more imprudent than running a train with two

engines a-head on such a plane at n high velocity, even over a road well consolidated by time, and the danger of such a proceeding is obviously most fearfully increased when it is

permitted on a line which has not acquired that degree of steadiness which is attainable only

from long use; and, while this practice is dangerous, it is not only altogether unnecessary, but expensive to the Company.

Your Lordship will readily perceive the utter impossibility of two drivers, however dexterous they may be, so regulating the speed of their respective engines, on such a plane as that on draw chains" of both uniformly stretched, and it is quite clear that when the leading engine sometimes draws the other, and is sometimes pushed by it, an irregular motion must result, having a tendency to disturb the balance of the leading engine, and more especially if that engine be the lighter, and carried by only four wheels.The risk is much increased on a line where the evenness of the rails has been disturbed by bad weather.

In calling the attention of the London and Brighton Company therefore, to the necessity of a

considerable reduction in their rate of speed on the falling gradients, and of paying constant

and close attention to the state of their road, I would recommend that they should be urged to discontinue the use of the assistant engine in the descent of their long inclined planes.

A most important and very safe practice prevails on some of the northern railways, which

should be immediately introduced on the Brighton line, and ought to be adopted on ail those

of recent formation, as it affords an excellent, constant, and almost unerring check on the

contractors. who are generally held responsible to maintain the road in good order for 12

months after the opening:

The practice to which I allude, is that of making each policeman carry a gauge, and walk over his beat, before the arrival of every train, trying the gauge of the rails in such a number of points as to ascertain whether the line is throughout in perfect order; and it is the policeman’s duty to stop a train, or give the signal of caution, according to the degree of risk he may discover.

I find that the point where it is presumed the engine first became irregular in its motion, just

before the accident, in one to which I had called the especial attention of the Company, as

requiring careful and cautious driving and watching.

Professor Barlow very justly observes, that it will be the rase on the London and Brighton, as it is on all new lines, that for some time to come fresh weak points will be produced by

unfavourable weather, and I therefore conceive it will be proper not only to press upon the

Company the necessity of devoting the most vigilant and unremitting care to the state of their works generally and of the permanent way in particular, but that it will be indispensably necessary that this line, on which so large a traffic may be expected, should have the especial attention of this department, and be occasionally inspected during the winter after had weather, in order that such suggestions may from time to time be offered to the Com any as may relieve the Board of Trade from alt responsibility as regards the public safety on this railway.

I have, &C.,

FREDERIC SMITH

Letter sent to the London and Brighton Railway Company,

with Extracts from Sir F. Smith’s and Professor Barlow's Reports.

October 19,1841

SIR, Board of Trade,

With reference to the late accident on the London and Brighton Railway, I am directed, &C.,

to inform you that their Lordship recommend to the Directors of the London and Brighton

Railway Company the adoption of the following precautions, which have been recommended by Sir F. Smith and Professor Barlow :-

l. That the speed in descending the long inclined places upon the line, and also upon all

portions of the line which may appear to be not perfectly consolidated, should he reduced,

and strict orders issued to prevent such limited rate of speed as is thought proper for safety

from being ever exceeded.

2. That with a view to this the time-table should be revised, and the average rate of speed

along the line, which is stated by Professor Barlow to be in some case as high as 25 miles per hour, should be considerably diminished.

3. That the practice of running trains with two engines a-head down long inclined planes,

should be discontinued.

Sir F. Smith further suggests, that a practice which prevails on some of the northern railways

might with advantage be adopted, as affording an excellent check on the contractors, who we responsible for maintaining the road in good order, viz., of making each policeman carry a gauge, and walk over his beat before the arrival of train, trying the gauge of the rails in such a number of points as to ascertain whether the line is throughout in good order, and making it his duty to stop or caution trains according to the degree of risk he may discover. Their Lordships recommend this suggestion for the consideration of the Directors.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

Sir, The dreadful accident on the Brighton railway on Saturday, whereby the maidservant and footman belonging to one family, the engineer and stoker, were , as I am informed by an eye witness, literally smashed to pieces, besides many others dangerously wounded, arose from there being two engines to the train, which ought never, under any circumstances, to be

allowed, either both in front or one as a propeller. A moment’s thought must convince any one of the danger. If both are in front, and second is in the slightest degree quicker than the other, it must naturally and inevitably push the foremost off the rails, as was the case on Saturday; and if one be used as a propeller, and the leader be checked in anyway, the carriages must be smashed between them. If the train be too heavy for one engine, either divide it, and let each part have an engine, following at a reasonable time after; or, what be preferable, let the company have a few engines of extra power to be used as occasion may require.

I was a passenger in a train meeting that which had the accident. It will scarcely be credited

that our train, and one which had arrived afterwards, were joined about to be despatched with two engines: and would have have been so, but that a gentleman in the carriage with me fortunately perceived it, and, after remonstrating wit the superintendent who would not alter it, saw one of the directors who after our protesting against proceeding with two engines, and telling him that he would be considered responsible if any accident occurred in consequence, had the train divided, with and engine to each.

I write in the hope that through your means the attention of Government, the directors of all

railroads, and the public may be called to this point, which will tend much to lessen the

danger of railroad travelling.

The use of two engines ought to be prohibited by act of Parliament; but until that can be

obtained it would be wise if the directors of all railroads would assure the public that two

engine shall never be used to one train.

I am, Sir, Yours,

J.F.B.

THE INQUEST

As published in

the TIMES Newspaper October 1841

On Monday morning a highly respectable jury was empanelled before Mr. F.H. Gell, Coroner for East Sussex, at the Railway Beer Shop, near Haywards Heath station, to investigate the circumstances attending the melancholy loss of four lives, which occurred on Saturday last on the railway, owning to one of the engines running of the rails. The jury comprised Mr. T.J. Bellamy and Mr. N. Barwell, two of the magistrates for the county of Susses; the Rev. W.H. Scwabe, curate of Cuckfield; the Rev. H. Fearson, master of an academy at Cuckfield; and the most respectable inhabitants of Cuckfield and the neighbourhood.

Mr. Faithfull, of Brighton attended to watch the proceedings on the part of the railway

company. There were also present, Mr. Harman, Mr. Robinson and Mr Heaviside, directors of the company.

The jury having been sworn, proceeded to view the bodies, which had been deposited in a

beer shop about a mile to the north of the station. The names of the deceased were Robert

Marshall and Robert Field (the firemen of the engines which propelled the train), and Harry

Palmer and Jane Watson (servants of Dr. Carpue, the celebrated anatomist). The bodies had

been placed in a carpenter’s shed, and presented spectacle.

Having viewed the bodies, the jury proceeded to an adjoining beer shop, where the drive of

one of the engine was taken immediately after the accident. He appeared to be fast

recovering.

The Coroner administered the oath to him, and he proceeded to make the following

statement:-

Charles Goldsmith. On Saturday last, on arrival at Horley of the 11 o’clock train from

London, propelled by a six wheeled engine, a second auxiliary engine was put on to assist the train to Hayward’s Heath. It was a four wheeled engine, and I was the driver. The train was a very heavy one, and, I believe, was a little behind time. My engine was put before the other, and we proceeded at the rate of about 30 miles an hour. When we reached the Copyhold cutting, I received a different motion in the engine, which wavered backwards and forwards. I don’t know what followed, I was stunned and heard nothing more. The motion lasted only an instant. When I recovered I found myself n a ditch covered with sand and water under the tender. Some persons were removing the tender as I came to myself, and told me that the accident has happened about ten minutes. It was my duty to examine the engine before it left Horley; I did examine it, and it appeared to be quite safe. When we got to Copyhold, the driver of the first engine let off his steams; and I turned off mine to within half an inch. The other engine was doing nothing; mine was doing but little, merely keeping the chain tight.

There was no policeman in the cutting. The last policeman that I saw was at the Ouse Valley

viaduct; and he signalled “all right.” I did not expect to meet another policeman till I got to

Hayward’s Heath. It is customary to put on a second engine at Horley when the train is heavy or behind time. The action of a small and heavy engine is the same; but a heavy engine holds it was longer than a small one. If a driver is not very careful the large engine would cause a jerk against the small one when the steam was shut off. Never knew an instance of the first engine being thrown off in this way. Two engines of different powers and weights can run together at the same speed. I am in 21st year. I have been employed on locomotives for five years; but have been a driver only a month. I was competent two years ago. I shut off my steam because I thought I saw a man in the cutting hold up his hand. The other driver had shut off the steam previously. I understood the signal to be to slacken the speed. Where the road is not heavy, we are in the habit of going at the rate of 30 miles an hour. I felt no bumping when the steam was turned off; I could not, as the hind engine was not drawing. I have printed instructions from Mr. Hurst, but they contain no directions against speed except on the Croydon and Greenwich lines.

Examined by Mr. Faithfull. I was to have left the train at Hayward’s Heath. I was three years

on the London and Birmingham Railway, and never knew any other four wheeled carriages

used there. If one of the wheels of the engine had become loose, such a motion as I felt would have been consequence. This might have been the cause of the accident.

John Holland, a retired officer in the army, who identified the bodies of Henry Palmer and

Jane Watson, the former as the footman; the latter as the housemaid, of Mr. Joseph Constantine Carpue, surgeon, of Upper Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, whose family he had been in the habit of visiting . Henry Palmer was about 23 years of age and Jane Watson about the same age.

James Jackson. I am an engine driver in the employment of the London and Brighton Railway Company. On Saturday last I left Horley at 5 minutes after 12 o’clock. Was to proceed from Horley to Brighton. I had brought the engine from Horley n the morning and was to return with it. i examined the engine at Horley, and it was in complete working order. A pilot engine was attached to the train at Horley, because we had heavy train, and to help us up the hill. We came from Horley to the Copyhold cutting at the average rate of about from 26 to 30 miles an hour. About half a mile before coming to the Copyhold cutting we were running at the rate of about 30 miles an hour. On entering the cutting by the bridge we do not exceed 23 miles an hour. I believe it to have been 20 or 21. Nothing occurred here to induce me to slacken my pace. I had shut off my steam half a mile before I came to the cutting, because my engine was getting slack of steam; as we were going down hill, and other engine was going to leave me at Hayward’s Heath. I wished to reserve my steam, that I might keep a good supply with which to get to Brighton. I did not observe any signal before entering the cutting. After we entered it, just before the accident took place. I observed a man, amongst a number of men, standing with one arm up; that is a signal to slacken speed. The instant we passed the man I observed the first engine rocking very much, and, directly after, she capsized right over to left hand side. I immediately leaped behind the fire box, and laid hold of the handle of the regulator, till I was thrown back by my engine coming into contact with the end of the engine. if the other engine had rolled a foot further, I think we might have avoided her altogether. I did not perceive the slightest movement in my engine till she struck the other. I was thrown back on the carriage of the tender, and continued holding the chain till the carriages stopped. It was all over in half a minute. We had no warning nor any thoughts of the accident. Directly I got off my engine, I saw one of the guards lying on the ground on his back close by my engine. I lifted him up, and then went back, and the next person I saw was Charles Goldsmith, covered with sand and mud, and under the frame of the tender in a gutter by the side of the road. We pulled him out of the hole, and the next person I saw was Robert Marshall, a stoker to the first engine, lying dead on the ground on his back, he lying lengthwise to the railway, with his head towards London. Seeing no other person, I got through the carriages, and then found Field, my stoker, about three yards from the carriages, between the out rail and the gutter. He

was almost lifeless; the phlegm was gurgling in his mouth. I told him to spit it out, and he did so. Directly I left him I proceeded to my engine, and saw a female lying across the railway, with a carriage wheel resting on her. She was with her face downwards, quite dead. At this time some men were getting Henry Palmer from under some carriages, within a couple of yards of the female. He was quite dead. The earth in the cutting is of a greasy nature, and a number of men, who are employed there, are in the habit of walking over the trams with their boots, leaving a portion of earth on them; which, in my opinion, was the cause of the accident.

Coroner. How would that affect the engine?

Witness. The engine being four wheels, and sliding about, and being top heavy, the gushing

about of the water on the top of the fire box would almost force her over. That is my firm

opinion. As to the state of the cutting, I have ran 30 and 35 miles an hour through it many a

time. The earth has nor given way at this part at all. All I saw was the rocking motion, which

I conjecture was owing to the slippery state of the rails. You do not feel this with a six

wheeled engine. I have been over there at 30 miles an hour and never have had any cause to

slacken speed.

Coroner. If there had been no pilot engine would the danger have been less?

Witness. I do not think my engine would have gone off, on account of its weight and having

six wheels. Only three carriages, those next to the tender, were thrown off the line. The others were not affected. Thee were 11 or 12 carriages in the train. I do not know how many

passengers; but there seemed to be a considerable number, and a good deal of luggage.

Mr. Barwell. do you consider the construction of the pilot engines safe or unsafe?

Witness. I consider them unsafe. There is a difference of opinion among engineers; but I don’t like four wheeled ones. This was as safe as other four wheeled engines, but I prefer six

wheeled ones. I think a four wheeled and six wheeled can act in unison together, if the stroke be the same. If a six wheeled and four wheeled were stopped at the same time the six wheeled engine would stop sooner than the four wheeled, because there would be less friction. Goldsmith took no notice of me, but shut off a part of his steam shortly after me.

Cross examined by the Rev. Mr. Fearon. I don’t think there is more danger in having two

engines than one. If we had had two four wheeled engines on Saturday the consequence

would have been still worse. I am quite sure that my speed between the viaduct and the

Copyhold cutting, about three quarters of a mile, was not above 30 miles an hour. We were

behind time a little at Horley, but did not go above our ordinary speed. The pilot engine was

put on because we had a heavy train. The accident happened about half past 12.

By Mr. Barwell. A foreman is kept at Horley and Brighton to examine the engines. I saw Mr.

Hurst go round mine at Horley, and believe he looked over both.

By Mr. Allen. I am quite certain, from experience, that the slippery state of the rails would

cause, and not prevent, oscillation.

It is the same in chalk cuttings. I have been a driver four and a half years. Goldsmith was

perfectly sober, and I always knew him to be so. I can suggest no other cause for the accident but that iI have described.

By the Coroner. The weight of the carriages behind did not cause any movement in the

engine; it would make it go steadier. I saw a policeman at the viaduct give the signal “all

right,” but saw no other. The man who gave the signal was the foreman of the works there. I

never had signal there before. The engine went off immediately we had passed him. all the

engines are new ones. The pilot engine was in good working order.

Mr. Barwell. Did you ever state your opinion of four wheeled engines to any of the company?

No; not before yesterday.

Foreman. Have the engines ever run off the line before?

Yes; on Friday last I saw an engine, a four wheeled one, run off the rail at the Hayward’s

Heath tunnel. I did not know the cause. I have never seen any other case.

By Mr. Faithfull. When I saw the signal I pulled the retard lever, but it could not stop the

other engine.

By Mr. Barwell. I never knew a six wheeled engine go off the rail unless there was some

obstruction, or the points were wrong. The London Birmingham Railway uses four wheeled

engines, bu they are not so high as these and therefore require less heavy cylinders, and are

consequently less top heavy. I know a similar case to this occurring on the London and

Birmingham. they are made on the same principle, except that our boilers are larger. I should

not like to drive a four wheeled engine.

By the Foreman. Neither of the boilers exploded. That of the pilot was burst from falling

over. I observed the state of the rail after the accident. It was bent a little, a very little indeed,

owing to the carriages running against it. The rail was in the same state as that in which I had gone over it at 30 miles an hour, and believed it perfectly safe.

James Copley. I am a labourer employed on the railway. I recollect being Copyhold cutting,

about a quarter past 12 o’clock on Saturday last. I saw the down train coming at about its

usual rate. I made a signal to it to come steady just before they came to the bridge. We have

done it for the last three or four days on account of the wet, and for fear they should come

light. There was no reason more than the usual one. I did not see the accident. As soon as the train passed I went away.

Mr. Barwell. Were the rails greasy?

No, sir. In that part soil is sandy. There is some black clay at the top. I had been told to make

the signal by a policeman. There are veins of black soil running down the cutting. I had not

observed in particular the clay from the labourers’ boots on the rails.

Juryman. What do you mean by the road being light?

Why, the wet pushes the rails up, and makes them uneven, but that was not case with the rails on Saturday.

Mr. Faithfull then called.

Mr. John Hardy. I reside at No.3, Portland Place, and am member for Bradford, in Yorkshire.

I was a passenger by the quarter before 11 o’clock train, from London, on Saturday. I was in

the middle part of the carriage next to the engine, with an open coupee on each side. The first thing I experienced was a great shock and dreadful screams. I was in the middle of the

carriage, with my face to Brighton; and by the shock a lad, who was sitting in the corner

opposite to me, was thrown on my knee. There was immediately great crashing. I and my son in law, Mr. Wood, spoke to the ladies, when new were suddenly lifted and turned around, and, in the course of a few seconds instead of being with my face towards Brighton, my face was towards London, and the carriage leaning against a sandbank. Just as we were first struck a quantity of steam and water came into the carriage, but there was no escape for it. As soon as we were still Mr. Wood, who was next to the window got out, there being room between the window and hill, and assisted me in doing so. I immediately jumped across the ditch, and found the carriage had been completely turned round. I went round the engine, which was in the road, and the first thing I saw was the guard, very disfigured. I spoke to him, found he was still alive, and called for a surgeon. Mr. Elliott came. A little further on I observed the engine lying on the ditch, on the left hand side. A little beyond it was one of the stokers lying, apparently dead. I have travelled a great deal by railway. I have been 11 times by this railroad, and, to the best of my judgement, we were proceeding at the rate from 20 to 24 miles an hour, just before I had been complaining to my companions of the slowness of the speed, and said we should be half an hour behind out time at Hayward’s Heath.

By the Foreman. I thought this was a very long train. I had taken my place in the coupee, but

my son in law persuaded me, just before starting, to leave it. Had I remained most probably

your inquest would have been upon me.

By M.r Faithfull. I cannot give a scientific opinion upon the point, but from experience, I

should say the heavier the train the steadier the motion.

Mr. John Wood, of Thaddon Grange, Alton Hampshire, corroborated the evidence of Mr

Hardy. in going through the cutting, I should suppose the speed to be from 20 to 25 miles. I

frequently travel on railways.

William Beedham. I am a builder and surveyor residing in North Street, Brighton. At the time of the accident I was near the railroad, about half a mile from the place where it occurred. I heard the train coming. I took my watch out, and also the railway table to see what train it was. It was just half past 12. According to my judgement it was going about 25 miles an hour.

I had a full view of it across the viaduct, about half a mile from the accident. I could not say

whether it slackened before I lost sight of it.

Richard Hodges. I am a labourer on the railway and live at Copyhold. I saw the train, on

Saturday, in the cutting. It was coming along at the usual rate. I saw the first engine jump up

and down as it came along, it might be about half a minute, and then I saw it drop right off

the rail. I then turned and ran away; either the tender or the engine caught me, and one of the

stokers fell across me and knocked me into the ditch. When it jumped the fore wheels rose up and down. I did not see any oscillating motion.

Matthew Hall, assistant engineer. It is my duty to inspect that portion of the railway on which the accident occurred, and to see that it is in a proper state. I had inspected it just previous to the accident. I was a little advance of the train, in the cutting, at the time. The road was in a fit state for travelling at 25 miles. it was in as good a state of repair as it has been in since the line was opened. I am of opinion that a heavy train is steadier than a light one. I am stationed on the line for 16 miles, to St John’s Common, and it is in a perfectly fit state for travelling. I did not observe anything on the rail to make it slippery. The soil is sandy.

Mr. Elliott of the Brompton Lunatic Asylum, who had been a passenger by the train, and had

attended on the wounded engine driver and guard, had been subpoenaed, and was present

during the investigation; but as he was not able to give any additional evidence, he was not

called.

The Jury expressed a wish to have the policeman who was on duty at the Ouse Valley

viaduct, a mile north of Copyhold cutting, when the train passed, examined as to the speed at that time; and a messenger was despatched to summon him before the Coroner.

In the meantime the jury having expressed an opinion that the cause of the accident was the

use of four wheeled engines.

Mr. Faithfull said that Mr. Rastrick, the chief engineer, and Mr. Statham, one of the resident

engineers were present and ready to explain any matters which the evidence might have left

in doubt.

The jury, however, did not ask them any questions.

Jackson, the engine driver, re-examined. I think that the water and the top heaviness of the

pilot engine, coupled with the slippery state of the rails, was the case of the accident. I have

known four wheeled engines run off on the Eastern Counties line, but I never knew six

wheeled engines to do so.

John Hinge examined. I am police constable, No. 37, on the line of the London and Brighton

Railway, and reside at Cuckfield.

On Saturday last, between 12 and 1 o’clock, I was on duty at the Ouse Viaduct. I saw the

down train coming towards me, and held up my hand to give the “ all right” signal; and as it

passed me I gave a signal to go steady, as I observed that it was going rather faster than usual.

I did not at that time observe any particular motion of the engine or train. Shortly after I heard a great noise in the direction of the Copyhold Cutting and as I thought the bursting of a steam boiler. I ran in that direction as hard as I could, and some labourers ran also. As soon as I got into the cutting, which is about three quarters of a mile, I observed that an accident had happened, and I got up to the spot, and rendered assistance to the sufferers. I do not know how it happened. I had no apprehension of an accident occurring when I saw the train pass along the Viaduct. I did not say my heart came into my mouth when I saw the train coming along, they were going at such a rate. The road where the accident happened has been out of order lately in consequence of the bad state of the weather.

The court was here cleared of strangers, and at half past 6 o’clock the jury returned a verdict

of “ Accidental death, with a deadand of one shilling on the engines; and the jury are of the

opinion that the four wheeled engines used on this line are not of a safe construction, and they recommend their discontinuance.”

Sir, Observing that in the melancholy accident on Saturday last the passengers in the first

carriages were the only ones killed, which I recollect has generally been the case in all

railway accidents occasioned by the engine getting off the line, it has led me suggest, either

that the luggage of the passengers should be placed on one or two luggage trucks between the engine and first carriage, or else to have a break of some elastic material, say pass of wool made almost the length and breadth of one of the carriages, so that the first concussion would be on it, and not on the bones and heads of the poor passengers, though of course they must feel, but in a less degree, being at a greater distance from the engine than at present.

Hoping this suggestion may tend to the public good,

I am, Sir, YOUR CONSTANT READER