Railway accident on the

L.B.S.C.R.

EASTBOURNE BUFFER STOPS COLLISION

On 26th January 1904, when a 'Gladstone Glass' engine No. 192 ‘Jacomb Hood’ ran into the

buffer stops when entering Eastbourne station with the 8.5. p.m. Hastings – London train in

pouring rain. No serious damage or casualties resulted, the engine retired to the shed. The

train continued in service with another engine a E4 class no. 485 ‘Ashington.'

The Third (Transitional/Tank) Shed 1904

This was the so called ‘Tank’ shed nicknamed by virtue of the water tank which stood on top a long single road shed. The exit to the north was straight onto a 45ft turntable, which lay right at the apex of the Horsham branch’s divergence from the main line, with two roads accessing to a reversing siding beside the Horsham lines. While the second shed was in operation, the Horsham lines must have been frequently occupied by locomotives crossing-over between the two servicing points.

When the widening of the lines and the extension of the station commenced and claimed the space and site of the second shed, the ‘Tank’ shed stood in until completion of the new shed sited a few hundred yards further south on the east side of the main line and close to the Horsham line. It became the ‘Engine Shed’ as indicated in the 1911 O/S map (right), and was converted from dead-end to through pattern permitting access via the west marshalling yard. A spur ran beside the coaling platform, and locomotives stood overnight in two sidings close to the shed and in the new short sidings close to the shed and in the new short sidings emanating from the turntable. The new depot was probably brought into use about 1904.

Loco No. 38 ' Millwall' photo taken outside Three Bridges Loco Shed in 1904

LONDON BRIGHTON & SOUTH COAST RAILWAY 1904

Number of Enginemen within the L.B.& S.C.R. 630 (including Motormen)

Wages for Enginemen: 34 - 48 Shillings per week, working day 10 hours and Promotion according to needs of service.

Wages for Firemen; 21 -27 per week, working day 10 hours and Promotion after six years

firing service.

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

Derailment at Littlehampton 1904

Railway accident on the

L.B.S.C.R.

Derailment between Cocking and Singleton

Friday 9th September 1904

Midhurst Driver William Dale

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

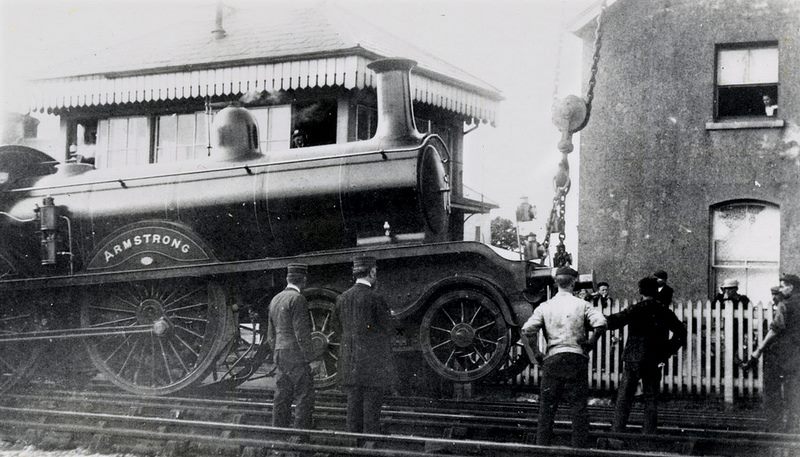

D1 Class Tank No. 239 ‘ Patcham’ worked by Midhurst driver William Dale, came to grief on Friday 9th September 1904. It was returning from a Midhurst to Singleton freight working when it left the rails for no apparent reasons, taking with it an open truck, box van and guard’s van, between Cocking and Midhurst (Cocking Causeway - 1 mile north of cocking, having just passed over Park Lane Underbridge). It was finally lifted back onto the rails two days later, on Sunday 11th October 1904 it was re-railed by steam cranes from New Cross (No.17) and Brighton (No. 16).

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

Railway accident on the

L.B.S.C.R.