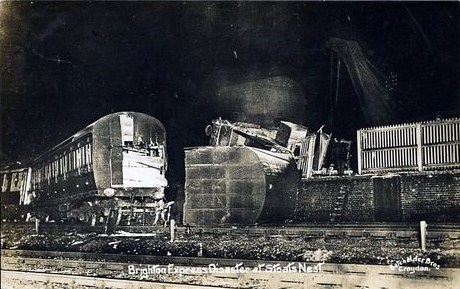

Railway accident on the

L.B.S.C.R.

Stoats Nest 28th January 1910

Involving Brighton Driver John Thompsett & Fireman unknown

SEE SUB PAGE

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

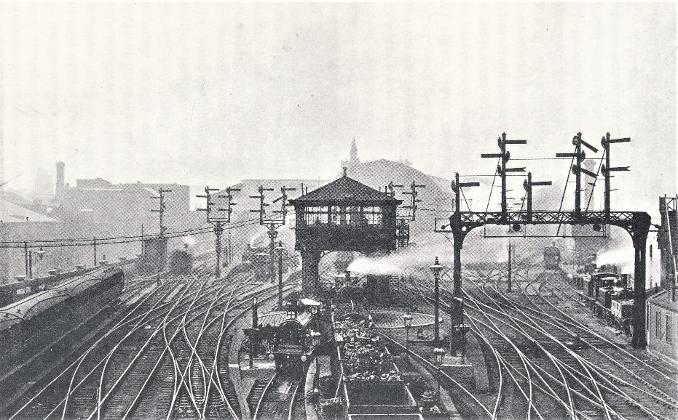

APPROACHING LONDON BRIDGE 1910

ELECTRIFICATION EXTESION

With the success of the electrification of the South London line the L.B.S.C.R were planning to electrify to Brighton using electric locomotives for their express services. But immediate priority was given to the suburban routes. Conversion of routes to Crystal Palace from both London Bridge and Victoria was decided upon in July 1910 with electrification operating between Victoria and Crystal Palace on the 1st June 1911..

The pictorial representations upon the certificate are designed to tell the story of the development of the means of locomotion, with which the Society is so intimately connected, from its earliest stage to its present advanced position. Honour is fully given to the two men whose genius so largely contributed to this development. On the left is shown a portrait of James Watt, the Scotch mechanician, who by his improvements upon the invention of Thomas Neweomer, a Dartmouth locksmith (the first user of steam as a motive power), so regulated the action of the Steam Engine as to make it capable of being applied to the finest and most delicate manufactures, and whose son, James Watt, made, in 1817, the engines of the first steam vessel which sailed from an English port.

On the right, appropriately appears a portrait of George Stephenson, the self-educated colliery fireman, who by his powerful genius became the founder of the great school of railway engineering.

Representative figures of Driver and Fireman are shown in fraternal greeting on the footplate of the Manchester, Sheffield, and Lincolnshire Railway Co.'s Engine No, 431.

Immediately above these portraits is seen "The Rocket," the winner of the £500 prize for a locomotive engine, to be used on the Manchester and Liverpool Railway; this, the first locomotive, was constructed by George Stephenson, and is now a national monument in the South Kensington Museum. This rude engine is brought into strong contrast with the wonderfully developed engines now in use, which are represented by a Great Northern Express, an express passenger train on the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway, and a Great Northern Piccadilly and Brompton Electric Tube Train.

The Certificate is also graced with emblematic figures of Justice, Agriculture and Commerce. Hercules, the symbol of individual strength, with lion couchant in subjection to him, and Vulcan, more usefully employed in forging couple-chains than thunder-bolts.

A Bee-hive is also introduced, as a type of the industry and united action of the members of the Association; and the peace and harmony existing amongst them find fit emblems in two harmless doves.

The Certificate also shows the way in which the hindrances to communion and commerce, arising from the long distances between centres of population, are now practically annihilated, by illustrations of the modes in which communication is kept up between manufacturing, mining, and other inland industries, and the shipping ports, and, through the latter, with all the accessible parts of the known world.

The possessor of this Certificate is therefore reminded by it of the important part which he, as a member of the "Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen," individually plays in the vast chain of intercourse between man and man the wide world over, and upon which all progress in Art, Science and Literature, and the diffusion of the advantages of civilization, largely depends; as well as in the multitudinous exchanges of commerce, the source of commercial prosperity and well-being of our nation, and lacking which, life itself in our large communities could not be sustained.

Mark Organ donation (June 2023) purchased this draw of the updated membership certificate, at a antique fair.

The certificate has been donated it to the A.S.L.E.&F. Head Office collection.

BRIGHTON

ENGINE CLEANERS c1910

Extracted & adapted from the book

By Fred Rich

Yesterday Once More

When two cleaners were put to work on the same engine, each cleaner would look after his

own half of the engine and the longitudinal line was their common boundary. It was a firmly

established tradition that the senior cleaner would clean the driver’s side while the junior

cleaner would clean the fireman’s side. On the Brighton engines the driver occupied the left-

hand side of the cab and this was known as ‘the lever side’ because the reversing wheel or

lever was located there: the fireman’s side of the engine was referred to as ‘the donkey side’

because the Westinghouse ‘donkey pump’ was normally mounted in a suitable position on that side.

On nights when most of the engines were on shed, they stood in long rows, buffer to buffer.

They were arranged (as nearly as possible) according to the order in which they would leave

next morning, but mean while it was totally impractical to move them. While they stood there, during the night, their cleaners went over them very thoroughly; but in many cases it was impossible to clean the upper most parts of the coupled wheels, these being up out of reach behind the splashers or inside the tanks. In due course, when the engine was movable, it would be positioned with the uncleaned areas of the wheel down at the bottom, this was

commonly know as 'half-turns'. Then, if the night cleaners were still on duty they would finish the job; otherwise the cleaners on day-work would be called along to do it.

The night cleaners were on piecework and received a fixed payment for any given task – so

much for cleaning a set of motion, another amount for cleaning a tender and so on.

From time to time a cleaner would also be sent out with a calling-up job. It might be that a

certain driver was due to book on at (say) 4 a.m. and he had requested a call at 3.15 a.m., so

the foreman would come looking for a cleaner to run the errand.

Even if the cleaner’s work was passed by the foreman it still might fail to satisfy the driver

when he came in the next morning.

In the preparation of his engine he had to go underneath the engine with his oil-can and if he

found any dirt – or worse still, soiled his clean overalls – he was likely to go to the foreman

and complain.

The day time cleaners would be required to clean goods engines which at returned from their night time work. The goods engine did not have any regular cleaners unlike the passenger engines. Another job for the daytime cleaners was to wheelbarrow coal from the loco yard to the East side of the station to keep a small reserve of coal for the engines that were working on the Kemp Town branch line.

By standing arrangements there was always an engine-cleaner would be ‘on loan’ to the

offices of the locomotive headquarters which were situated in the locomotive works at

Brighton. The duties which they performed were those of a messenger lad cum general office assistant. An engine cleaner for this assignment would require to be intelligent and of a smart appearance and they would normally serve in this capacity for a spell of twelve to eighteen months.

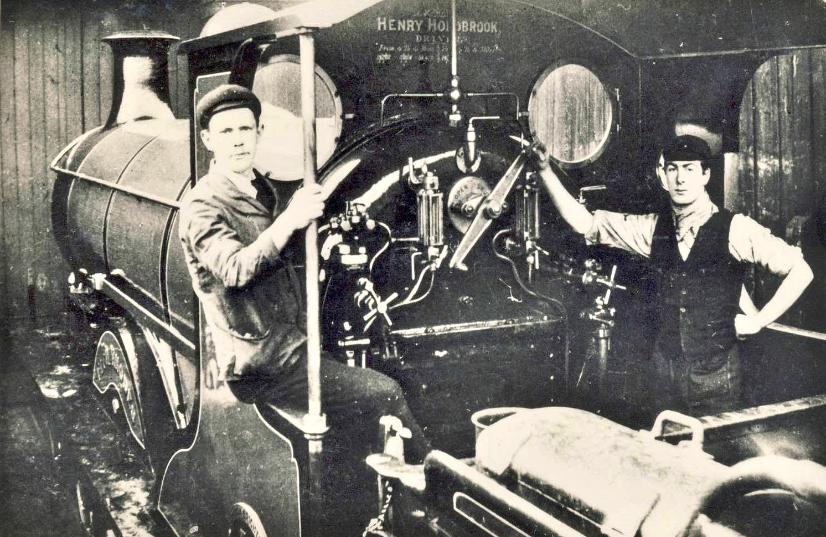

FRED RICH COLLECTION

Brighton Engine Cleaners c1911,

this engine was allocated to Brighton driver Henry Holdbrook

BECOMING A FIREMAN

Extracted & adapted from the book

By Fred Rich

Yesterday Once More

A newly "Passed Cleaner" could expect a long wait for the future firman's vacancy which would bring his appointment. A "Passed Cleaner" could wait could last two, three or four years, possibly even longer to get his promotion: and during that time the "Passed Cleaner” was a spare man, notching up only the occasional firing trip to begin with. Then, as time went by, he would be called out more frequently, say once or twice a week and he eventually he would be out firing almost every day as he approached the head of his queue for a vacancy. Meanwhile he was paid 3/9d only for firing turns, and 3/3 for all those days which he would spent "on shed." The difference of 15% was quite significant and the ambition of every "Passed Cleaner” was to complete 313 firing turns - an achievement which qualified him for the fireman's rate of 3/9d even though he was still unappointed. This figure of 313 was great significance to every generation of firemen right down to the end of steam, and continued through to the end of the second-man's grade (the second-man's grade ceased 2nd October 1988): it represented one year of working days (i.e. 365 days minus the 52 Sundays).

If a "Passed Cleaners" was consistenly bad he soon acquired a certain stigma; and when a firing turn cropped up some of the drivers began to demur - "I'am not taking him!" But if you were in shaping up well as a firman you began to be talked about among the drivers - and then you got plenty of firing jobs! It was this kind of reputation which, in later years, could take a first rate, experience firman to his place among the elite. In those days, unlike later times, seniority was not the only factor which determined a man's progress up through the different classes of work. A really good driver would be given one of the top locomotives handling prestige passenger trains, while a less adequate man might remain on secondary passenger services, goods work or even on shunting duties. By the same token, no driver wanted to work with mediocre fireman, but the really good firemen were in great demand. The top drivers wielded a lot more influence and were able to choose from those senior firemen who were most highly regarded. And of course, if a driver kept telling his colleagues " My mate can do this, my mate can do that!", then his mate was likely to be 'snapped up!'

PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

THE FIREMAN'S HELMET

Extracted & adapted from the book

By Fred Rich

Yesterday Once More

When a "Passed Cleaners" completed 313 turns (or when he received his appointment, which ever came first) he was issued with an engine man's cap to signify that he had "made the grade". These caps - or "helmets" as they were called on the L.B.S.C.R. These helmets were not cheap costing 7/6d which was considerable sum of money. It is understood that the

railway company didn't have to pay for the engine men's helmets: they were purchased from a fund bequeathed by the late Sir Julian Goldsmid, a former Deputy Chairman of the

L.B.S.C.R. In acknowledgement of Sir Julian's generosity and prestige, the engine men’s

copper cap badge portrayed Billinton D3 Tank locomotive No. 363 'Goldsmid'. It was

traditional for a “Passed Cleaners" to provide his own head-wear until he qualified for a

'helmet' by completing 313 firing turns. The make-shift garment was usually a cloth cap,

probably the same one which its owner had worn when he was a cleaner.

Railway accident on the

L.B.S.C.R.