Following approaches by A.S.L.E.& F., Army Council decision not to call Enginemen to the Forces unless and until required for a Transportation Unit.

Agreement reached on provision of lodging allowance for men moved owing to redundancy.

House of lords allowed A.S.L.E.& F.’s appeal in the compensation of Bro. E. Noble, deceased.

War increase in pay secured for Enginemen.

The historians have recorded very little of the importance that the railway's played during the war. This page, in the coming months, will try to explain the important role played by the enginemen. Although being an enginemen was classed as a “Reserved Occupation” and as such they could not be conscripted into the armed forces they were all expected to enter the Home Guard so not only were they working very long hours at work they were then expected to spend many more hours guarding their Depots and Sidings. The enginemen were putting their own lives at risk, whilst carrying out their work and keeping the country moving, whilst hostilities where going on all around them. Some engine men paid the ultimate price, as they come under attack from enemy aircraft.

The politicians promised all of Britain’s railwaymen and woman that after the war was over they would be rewarded for their commitments for keeping the trains moving around the country. The railwaymen and women were going to go beyond their normal expectations and at times too confronted with some of the most difficult circumstances that they would never expect to endure under normal circumstances. It was not uncommon for Enginemen to be on Duty for 24 hours only being relieved when they had run out of food and water!!.

During the Second World War, holidaymakers using the lines to the Channel ports and the West Country were replaced by troops, especially with the threat of a German invasion of the south coast in 1940. Before the hostilities began, 75% of traffic on the Southern Railway was passenger, compared with 25% freight; during the war roughly the same number of passengers was carried, but freight grew to massive 60% of total traffic. A desperate shortage of freight locomotives was remedied by C.M.E. Oliver Bullied with the introduction of the C1 “Austerity” Class Locomotive on the Southern Railway while the volume of military freight and soldiers moved by a primarily commuter and holidaymaker carrying railway was a breath-taking feat.

The British evacuation from France has been extensively documented but the historians have done less than justice to its sequel, which involved another 'evacuation'. This one was by land on our side of the Channel. All those troops had to be disembarked at various ports along the Kent and Sussex Coast from where they would be moved by train to place all over England. The railway was still by far the predominate system of land transport; and the German Air Force, with a few well-placed attacks, could have served our Southern railway links to the ports and caused total disruption to this second evacuation. It is anybody’s guess what would have after that, fortunately this did not happen.

In the Spring of 1940, the Germans had conquered France in a six week blitz offensive. This left the British Expeditionary Force with its back to the sea, trapped on the beaches of Dunkirk. It is now a matter of history that most of our beleaguered army was saved: as armada of rescue craft (including ‘the little ships’) swarmed across the English Channel to pluck our soldiers from the beaches of Northern France. This was Operation ‘Dynamo’ which took place between the 27th May to the 6th June 1940, ‘the miracle of Dunkirk', which left Britain to fight another day.

The railway companies had only a few days to prepare and to co-ordinate for this huge operation and at any moment those days might have dwindled to hours, to co-ordinate all their Locomotives, rolling-stock and train crews and had to produced virtually ‘out of a hat’.

The Dunkirk trains would require immaculate organising and the trains had to be brought together to be in the right place at the right time – and then keeping them moving along hastily – improvised paths.

Nobody could foresee just how soon the evacuation would begin – it was imminent all the time. Moreover, it was impossible to predict how many soldiers would be rescued from Dunkirk and how many would be left behind. The only course was to plan and pray for the maximum number to be brought home; and on this basis it was estimated that 150 trains would be required. It was envisaged by the War Office that the British Expeditionary Force – or whatever was left of it – would be disembarked at eight Southern coastal ports: Margate, Ramsgate, Dover, Folkestone, Hastings, Eastbourne, Newhaven and Brighton. From these places the movement of rail would begin and the travellers themselves would be no ordinary passengers: they would be dishevelled survivors who had escaped from Hell, and many of them would be wounded.

The evacuation trains were eventually seen on all four of Britain’s main-line railways, heading for various destinations. But they all had to start from a handful of stations along the South Coast; and before doing so they, they had to enter this congested area as empty coaching stock. Hence it was on the South Coast that the drama was enacted out in its entirety.

The movement started at dawn on May 27th 1940, and it took 186 trains and not 150 trains as planned for. The trains never stopped for nine and half days with the enginemen working continuously throughout. The evacuation trains moved 323,000 men away from the ports and across the country to safety. The enginemen on trains were coming into the stations, were dazed with weariness. It didn't make it easier for the railwaymen and women, that the ports weren’t quite the same as the Railway had planned for. Of course, the railway workers didn’t know anything about it at first, until the first train had arrived in the station, before they realised what was happening.

A.S.L.E.F. along with the NUR applied for an increase in wages for Railway staff in November 1940. In May 1941 Enginemen were awarded an extra 4s per Week taking the War Advance to 11s per week.

The engine cab where Enginemen almost lived day and night, were shrouded from the cab

roof to tender-end by the obliterating anti glare sheet, which not only trapped the revealing

glare from the engine's fireboxes, but kept the heat in as well. Enginemen would end up

suffering from heat rash, as if they had just emerged from a baker's oven.

There were instructions given to Enginemen at the beginning of the war - to seek cover when air-raid warning came along - was not, in practice, a success. To stop the railways

intermittently simply could not be done, and so it soon became general to treat that red

warning as nothing more or less than indication to be on alert. Even the tiniest blink of light

from the engines was blanked out as the Enginemen crept through a blackness which almost

be felt. Enginemen were also instructed how to immobilise their engines in the event of

enemy invasion. The people who issued this instruction, would have been surprised if they

had if they heard some of the ribald remarks with which it was greeted, for the officials of the company did not realise just what it meant to a driver and fireman to be told to sabotage

their engines, they had regarded for as sacrosanct.

During the Second World War 11, 35,000 Southern railwaymen who, while carrying out on their normal and often abnormal duties during the War, as members of the Southern Railway Home Guard, an efficient force to protect the railway against from the enemy. The Southern Railway Home Guard, although part of the National Home Guard, was a distinct railway organisation, being special authorised by the War Office, on offer made by the Southern Railway General Manager, Sir Eustace Missenden, in response to the government’s request to the railways for special precautions to be taken against enemy parachutists and saboteurs. Though separate from General Service units of the Home Guard, the S.R. units were affiliated, according to locality, to the appropriate County Regiments.

During 1940, things were going very badly for the Allies and, with invasion a possibility, the Secretary of State for War, Anthony Eden, made his appeal for volunteers to defend the home land. Southern Railwaymen of all grades, barred from by their calling from joining the more active forces, enthusiastically offered their services. The Southern Railway gave them every encouragement and the General Manager allocated experienced officers and staff to act as whole time organisers of the Local Defence Volunteers, as they were at first designated. Lt. Col. G.L. Hall, the Assistant Engineer (Signals and Telegraph) was appointed chairman of a committee of action, enrolment forms were distributed, and in less than a week the forced totalled 18,000. This number remained practically constant throughout the War, the figure of 35,000 first mentioned being caused by the comings and goings into the active forces and into retirement.

The Southern Railway was divided up into six sections and six battalion commanders were appointed. after the L.D.V. became the Home Guard in 1940, and military rails were used, the six battalions became part of the regiments of their respective counties, as follows:-

1st S.R. Bn 28th Kent Bn. Home Guard

2nd S.R. Bn 25th Sussex Bn. Home Guard

3rd S.R. Bn 12th Surrey Bn. Home Guard

4th S.R. Bn 21st Hampshire Bn. Home Guard

5th S.R. Bn 22nd Devon Bn. Home Guard

6th S.R. Bn 36th London Bn. Home Guard

His services being otherwise required by the railway, Lt. Col. Hall relinquished the leadership of the organisation and F.J. Wymer, then Assistant Continental Superintendent of the Southern Railway, was appointed to the rank of Group commander. Col. Wymer remained Group Commander until the end of 1943 when he took up an army appointment and his successor was the 1st Bn Commander Col. S.H. Isaac, with the tittle of Commander, Home Guard, Southern Railway.

The training of the Southern Railway Home Guard usually took place locally, not only for the convince of the men ands as not to interfere with their normal duties, but because their defensive area was local, and it added to their efficiency to have a thorough knowledge of their terrain, including local strong and vulnerable points.

A training centre for the whole Souther Railway was, however, set up at Gomshall on land joining the station, and at this camp throughout the war members of the Southern Railway Home guard, and particularly officers and N.C.Os., came to receive the specialised training which they were afterwards able to impart to their men. The camp at Gomshall was manned by Southern Railway staff allocated wholly to the Home Guard, with addition of instructors from the regular army. Similar centre were arranged at Brockenhurst, used principally the the 4th Bn., and at Chatham by the 1st Bn. Every kind of infantry weapon was used at these three centres and many of them, particularly those which had to do with anti-aircraft defence, were on the Secret list until late in the war. To those training centres came Travelling Wings of Instruction from the war office and from other branches of the services. The methods taught were afterwards spread amongst the ran and file all over the system.

Special attention was given to anti aircraft and as early as 1940, during the blitz on London, this training proved its use, while during the subsequent air attacks on other parts of the south of England, Southern Railwaymen were often in action. At Eastleigh a number of the 4th Bn. were detached to form the B Troop of 71st Isle of Wight and Hants Heavy A.A. Battery, while at depots throughout the Southern system 17 Troops of Light A.A. Defence were formed by the various battalions, who manned posts at night and were also available during periods of possible daylight raids to man the gun immediately an alarm was given.

Although war time travel difficulties prevented the holding of many inter-battalion contests, nevertheless competitions covering efficiency, shooting, field work, etc., were continually being held. There was a comradeship at these meetings which will endure a long time, and the spirit of friendship was strengthened by the social gatherings arranged for the winter evening. At these events there was alway a thought for the man at the front or the man in captivity, and every battalion was proud of the sums of money they were able to raise for the Regimental or Southern Prisoner of War or for comforts for the Merchant Service or those in the field of battle.

With fitness and preparedness the main them, ceremonial occasions were infrequent; nevertheless when occasions arose such as during the Wings for Victory, Warships and Salute the Soldier campaigns, members of the Home Guard units gave valuable assistance to local authorities by organising exhibitions, going in town parades and otherwise helping the cause. And at times of air raids they co-operated with local rescue squads.

Recognition by the government of the value to the defence services by the Southern Railway Home Guard was reflected in the honours lists. These included one C.B.E, five M.B.E., two B.E.M., one George Medal, over fifty C.-in-C. certificates for meritorious service and one Commendations for brave conduct.

Railway accident on the

Southern Railway

TUNBRIDGE WELLS BRANCH 1940

Driver C. Pattenden of Tunbridge Wells Branch was killed when his train was bombed and machine gunned by a German plane: he was the first of many which went to prove the "lines behind the lines" were not so very far in the rear.

Taken from

“The Lighted Flame”

On Wednesday 3rd July, 1940 the 17.37 train from Seaford was machine - gunned between

Bishopstone to Tide Mills. The driver, Charles Pattenden was killed but the passengers ducked down and tried to under their seats. The aircraft then dropped six bombs nearby which shattered the windows of the carriages and injured several passengers. Mrs May Terrrill of Newhaven who said afterwards, “It happened so quickly. All the windows were smashed and had lots of splinters of in our hair. My son Ronald (later to become a driver at Newhaven & Brighton) a babe in arms had a cut neat one eye and the back of my coat was marked as if it had been scorched."

BOMB DAMAGE TO BRIGHTON SECTION OF THE SOUTHERN RAILWAY

Extracted from Blood & Custard Website

Portsmouth Harbour Monday 12th August 1940

Ford Saturday 31st August 1940

Peckham Rye Monday 9th September 1940

Streatham Hill Saturday 28th September 1940

Reigate Friday 20th September 1940

Fratton Depot Wednesday 25th September 1940

STORIES FROM THE SHOVEL

Two firemen Graham White & George Howes

who were formerly of Bognor Locomotive Shed.

Extracted from the book Going of the rails

Graham and George both joined within months of each other in the early 1940. At this time Bognor was still a sizable engine shed under the rule of the Running Loco Foreman, a Jack Tribe, whose characteristics including a large moustache and a penchant for smoking a vile herbal tobacco. Twenty – two sets of men worked from Bognor shed which provided motive power for goods trains, including the Chichester to Midhurst goods turn.

Both men started as engine cleaners but a shortage of manpower meant that spare fireman were allocated to a firing duty as required, and the following day reverted to engine cleaning duties. The cleaning shifts were 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. and 2 p.m. to 10 p.m. Even though Graham and George had fired engines on the line they were not allowed into the Driver’s and Firemen’s’ Lobby. To again admittance, a cleaner had to become a Passed Fireman. That was achieved once he had completed the requisite number of 313 firing duties. In the meantime, to emphasise their exclusion, a detonator was dropped down the chimney of the Lobby and loud explosion ensued!

The requirement for a Passed Cleaner to complete 313 firing turns to qualify as a Passed Fireman had remained the same since the days of the L.B.S.C.R. Before 1923 it could take several years to notch up the required turns.

There was no shortage of manpower and young men remained cleaners for years before firing an engine on the line.

BOMB DAMAGE TO BRIGHTON SECTION OF THE SOUTHERN RAILWAY

Extracted from Blood & Custard Website

Peckham Rye Depot Wednesday 2nd October 1940

Beckenham Junction Thursday 3rd October 1940

Nr Bromley Junction Wednesday 9th October 1940

Victoria Wednesday 9th October 1940

West Croydon Thursday 10th October 1940

Bookham Friday 11th October 1940

London Bridge Monday 14th October 1940

Selhurst Depot Monday 14th October 1940

BOMB DAMAGE AT

SELHURST ELECTRIC SHED

Monday 14th OCTOBER 1940

BOMB DAMAGE AT WORTHING ROAD

OCTOBER 1940

(HORSHAM - CHRIST'S HOSPITAL)

It is understood that Horsham loco crew on this train were Driver Jack Budd and Fireman

Ron ‘Razor’ Reeves. The train was under attacked by a German fighter at West Grinstead,

and Razor had jumped off the footplate into a ditch which ran alongside the track, which

saved his life. The line was bombed and the train went down a bomb crater, and the driver

was Jack Budd who was killed. In later years Razor Reeves never talked about this incident.

BOMB DAMAGE TO BRIGHTON SECTION OF THE SOUTHERN RAILWAY

Extracted from Blood & Custard Website

New Cross Gate Thursday17th October 1940

Selsdon Friday 18th October 1940

Eastbourne Saturday 26th October 1940

Eastbourne Station bomb damage on Saturday 26th October 1940

BOMB DAMAGE TO BRIGHTON SECTION OF THE SOUTHERN RAILWAY

Extracted from Blood & Custard Website

Selhurst Depot Wednesday 30th October 1940

Gatwick Airport Monday 11th November 1940

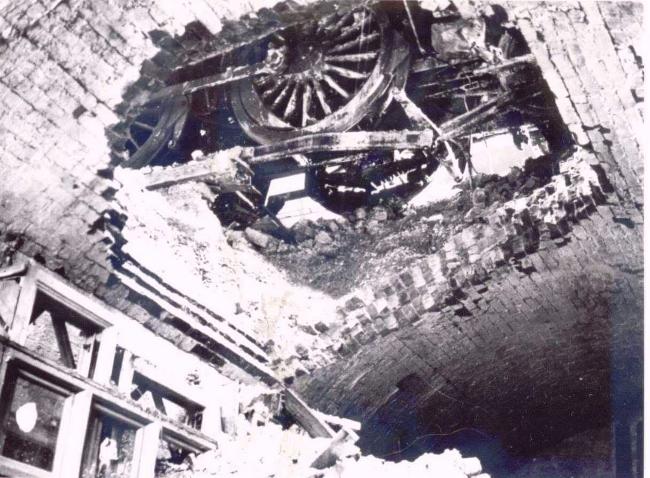

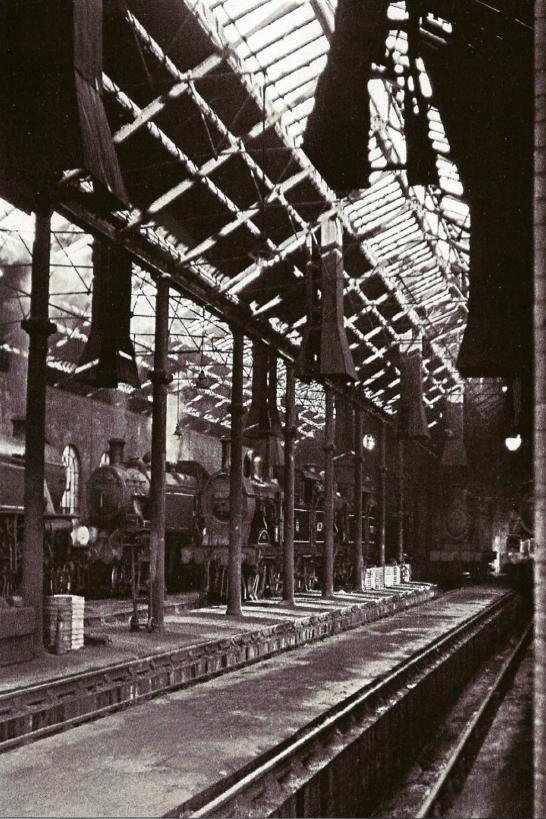

BOMB DAMAGE AT

TUNBRIDGE WELLS LOCO SHED

WEDNESDAY 20th NOVEMBER 1940

On 20 November 1940, at half-past-four in the morning, a German high-explosive bomb

fell on the running shed at Tunbridge Wells West. It caused a large crater between Nos. 1 and 2 roads (the lines shown here). Two locomotives were badly damaged, an '11x', No. 2007 and an '13', No. 2024. luckily there were no human casualties but a number of people in the nearby lobby were badly shaken up. All the glass in the shed was blown out and the blast didn't do the roof much good either. Both locomotives were repaired and put back to work but No. 2024 was withdrawn in November 1944, long before any of its classmates. Meanwhile the shed roof was patched up and lasted another 14 years before a new one was installed.

Information from The Fred Rich Memoirs Demob Leave 1955

Ray Young (former TWW Enginemen (1949) recalls.The running foreman on the night of the bombing was Mr. Smart (I think he was Albert). He was blown through a door way but not seriously hurt.

Newhaven Branch Meeting

Sunday December 15th 1940