FIRING ACROSS THE DIVISIONS

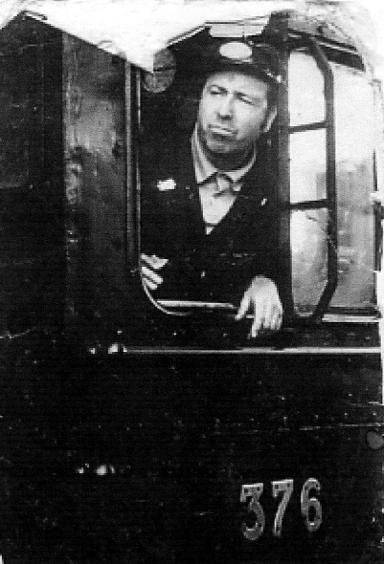

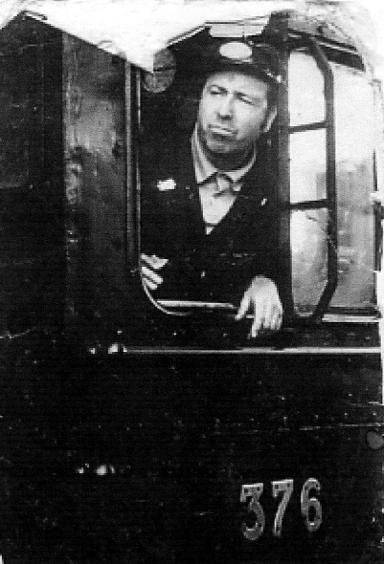

Norman Denty

Memoirs of Fireman Norman Denty 1941~1950

Curtsey of Neville Watts

Norman Denty

Curtsey of Neville Watts

CENTRAL DESPATCH

April 1940 I started work on the Southern Railway as a messenger boy, dressed in a smart black uniform and peak cap. I was with the Central Despatch Department. Who because of the bombing blitz on London, had moved with their office staff to Brighton, their new home was the old disused wheel shops in the locomotive works. The ground and first floors of the old shops were hastily converted to office use. The office staff now travelled daily from the city. Not long after the move came "Dunkirk". With the withdrawal of the armed forces from France came the new fear of axis armies invading the south coast of England. The offices that had been evacuated to Brighton now returned to London Bridge Station, to a nine-storey building at the end of platforms 18-22. Originally it had been a hotel for the London Brighton and South Coast Railway. I along with three other messenger boys that had started with me, now travelled daily to London.

On Saturdays we worked until 12:30pm, then along with three other messengers who lived in London we would go to Waterloo Station and become porters for the afternoon. This was allowed by the management, because we wore uniforms. In the summer of 1940, holiday makers were still going in their thousands to the resorts on the Isle of Wight, and to Hampshire, Dorset, Devon and Cornwall all served by the Southern, hard to believe after the evacuation of Dunkirk, but nevertheless true. Trains from those counties arrived continually on Saturday afternoons during the summer of 1940. Porters awaiting the arrivals were lined up on the platform from end to end of the terminus, and they all would get jobs carrying passengers' luggage, and often business was so good that we got more tips, by going back to the same train. The messengers could earn as much as their weekly pay in an afternoon, so it was well worth the effort, these were the good old days when tips were not taxed. Railway porters today are a rare breed, but one day there might be revived. Many passengers still have difficulty understanding train announcements over the loudspeaker systems at stations. It was just the same fifty odd years ago. I once knew a Spanish lady who lived in England for over ten years. She could not speak a word of English but got a job as a station announcer at Waterloo!

With the dark nights of the 1940 winter, the German bombers came back over London and, during the midday lunch breaks the messengers would go to the top of the offices and from there look down the River Thames to the dock areas and watch the warehouses on fire from incendiary bombs. Some warehouses would burn for weeks on end owing to the highly flammable type of materials stored inside them. Messenger work also consisted of rolling off printed notices from the "Roneo" hand machines, which with other letters were sent to all stations on the Southern Railway system. Letters for the "Foreigners" main line stations in London, of the G.W.R., L.M &.S.R. and L.N.E.R. went by road transport or, occasionally, if it was urgent, by messenger. Quite often it was difficult to get to London Bridge owing to the railway lines beyond Norwood having been blown up.

If this was the case, once the train had reached East Croydon it would be diverted to Victoria. From there the messengers from Brighton would go by tube to London Bridge. One particular day, the tracks above Norwood Junction were blocked, so the trains were now routed to Victoria, we reached Balham Station, but the tracks beyond had also been bombed.

If this was the case, once the train had reached East Croydon it would be diverted to Victoria. From there the messengers from Brighton would go by tube to London Bridge. One particular day, the tracks above Norwood Junction were blocked, so the trains were now routed to Victoria, we reached Balham Station, but the tracks beyond had also been bombed. The messengers now made for the Northern line to London Bridge, but that was out because of enemy action. Sadly many were killed at Balham underground station in the early hours of that morning; the death toll 164 and most were women and children.

There were no buses going to the Bridge for one reason or another, so we caught one for Westminster Bridge. On arrival there we walked to the pier on the river and boarded a river bus, with a London transport conductor collecting the fares, we left the water bus at Tower Pier. then we walked through Billingsgate fish market and on over the old London Bridge [which is now in America] to the station, somewhat late for duty. The management knowing the problems the Brighton lads had getting to work were always pleased to see us arrive, Getting home again was just as difficult. Our day normally ended at 5.00 p.m. but if there were no trains from the Bridge, that meant the tube for Victoria, contacting that station first by telephone to see if the trains were running. We always managed to get back to Brighton, even though it was often late at night. I will not forget the night when our train was slowly going forward near Croydon the train stopped, the bombs were literally whistling

down, the search lights flashing up into the night sky searching for the bombers, the anti-ack-ack guns firing at them like fury. Nearby the bombs were exploding, the noise was deafening, and then the carriage lights went out. The four messenger boys lay down on the floor, and their carriage was swaying and shaking. So were we! By the end of November, I had left the offices at London Bridge. Just as well, as at the end of December they were in ruins. Bombs had gutted he old L.B.S.C.R. hotel. The office personnel now took up residence in offices above Waterloo Station.

down, the search lights flashing up into the night sky searching for the bombers, the anti-ack-ack guns firing at them like fury. Nearby the bombs were exploding, the noise was deafening, and then the carriage lights went out. The four messenger boys lay down on the floor, and their carriage was swaying and shaking. So were we! By the end of November, I had left the offices at London Bridge. Just as well, as at the end of December they were in ruins. Bombs had gutted he old L.B.S.C.R. hotel. The office personnel now took up residence in offices above Waterloo Station.

On Saturdays we worked until 12:30pm, then along with three other messengers who lived in London we would go to Waterloo Station and become porters for the afternoon. This was allowed by the management, because we wore uniforms. In the summer of 1940, holiday makers were still going in their thousands to the resorts on the Isle of Wight, and to Hampshire, Dorset, Devon and Cornwall all served by the Southern, hard to believe after the evacuation of Dunkirk, but nevertheless true. Trains from those counties arrived continually on Saturday afternoons during the summer of 1940. Porters awaiting the arrivals were lined up on the platform from end to end of the terminus, and they all would get jobs carrying passengers' luggage, and often business was so good that we got more tips, by going back to the same train. The messengers could earn as much as their weekly pay in an afternoon, so it was well worth the effort, these were the good old days when tips were not taxed. Railway porters today are a rare breed, but one day there might be revived. Many passengers still have difficulty understanding train announcements over the loudspeaker systems at stations. It was just the same fifty odd years ago. I once knew a Spanish lady who lived in England for over ten years. She could not speak a word of English but got a job as a station announcer at Waterloo!

With the dark nights of the 1940 winter, the German bombers came back over London and, during the midday lunch breaks the messengers would go to the top of the offices and from there look down the River Thames to the dock areas and watch the warehouses on fire from incendiary bombs. Some warehouses would burn for weeks on end owing to the highly flammable type of materials stored inside them. Messenger work also consisted of rolling off printed notices from the "Roneo" hand machines, which with other letters were sent to all stations on the Southern Railway system. Letters for the "Foreigners" main line stations in London, of the G.W.R., L.M &.S.R. and L.N.E.R. went by road transport or, occasionally, if it was urgent, by messenger. Quite often it was difficult to get to London Bridge owing to the railway lines beyond Norwood having been blown up.

If this was the case, once the train had reached East Croydon it would be diverted to Victoria. From there the messengers from Brighton would go by tube to London Bridge. One particular day, the tracks above Norwood Junction were blocked, so the trains were now routed to Victoria, we reached Balham Station, but the tracks beyond had also been bombed.

If this was the case, once the train had reached East Croydon it would be diverted to Victoria. From there the messengers from Brighton would go by tube to London Bridge. One particular day, the tracks above Norwood Junction were blocked, so the trains were now routed to Victoria, we reached Balham Station, but the tracks beyond had also been bombed. The messengers now made for the Northern line to London Bridge, but that was out because of enemy action. Sadly many were killed at Balham underground station in the early hours of that morning; the death toll 164 and most were women and children.

There were no buses going to the Bridge for one reason or another, so we caught one for Westminster Bridge. On arrival there we walked to the pier on the river and boarded a river bus, with a London transport conductor collecting the fares, we left the water bus at Tower Pier. then we walked through Billingsgate fish market and on over the old London Bridge [which is now in America] to the station, somewhat late for duty. The management knowing the problems the Brighton lads had getting to work were always pleased to see us arrive, Getting home again was just as difficult. Our day normally ended at 5.00 p.m. but if there were no trains from the Bridge, that meant the tube for Victoria, contacting that station first by telephone to see if the trains were running. We always managed to get back to Brighton, even though it was often late at night. I will not forget the night when our train was slowly going forward near Croydon the train stopped, the bombs were literally whistling

down, the search lights flashing up into the night sky searching for the bombers, the anti-ack-ack guns firing at them like fury. Nearby the bombs were exploding, the noise was deafening, and then the carriage lights went out. The four messenger boys lay down on the floor, and their carriage was swaying and shaking. So were we! By the end of November, I had left the offices at London Bridge. Just as well, as at the end of December they were in ruins. Bombs had gutted he old L.B.S.C.R. hotel. The office personnel now took up residence in offices above Waterloo Station.

down, the search lights flashing up into the night sky searching for the bombers, the anti-ack-ack guns firing at them like fury. Nearby the bombs were exploding, the noise was deafening, and then the carriage lights went out. The four messenger boys lay down on the floor, and their carriage was swaying and shaking. So were we! By the end of November, I had left the offices at London Bridge. Just as well, as at the end of December they were in ruins. Bombs had gutted he old L.B.S.C.R. hotel. The office personnel now took up residence in offices above Waterloo Station.

THE TRAFFIC DEPARTMENT

I transferred to this department and was now a signal lad at Keymer crossing signal box, Burgess Hill, Sussex. It was a small but busy box with only twenty-one levers and some crossing gates. It controlled Keymer Junction where the lines diverged for Brighton and Lewes. Two signal men lived in the two houses across the tracks right opposite the box, and the third signal man lived in a house across the tarmac road Years before it had been a station house. The signalling on the Brighton line in the Keymer section were aspect electric automatic, and the junction signals were semi-automatic, as was the up line home signal, which meant the signal man could control them. From Clayton tunnel to within four miles of Haywards Heath the trains could be followed in both directions on an illuminated panel, indicated by a white light going out when the train was between signals, and when it passed them the white light came on again. The lines to Lewes and beyond had semaphore signals and between each signal box they had what was known as "Block Working". This system demands that there be a compulsory space interval between trains travelling in the same direction on the same line. Bell codes were used to describe the type of train from Keymer to the next signal box down the Lewes line, which was Spatham Lane. The signal lad booked the times of passing trains and when he was not there, the signal man had to do the recording. On early shift the lad had extra duties, i.e.:

Monday Clean the signal box windows.

Tuesday Shine up the handles on levers with emery cloth.

Wednesday Polish brass fittings with Brasso polish.

Thursday Scrub out the signal box and wood floor with soap and water.

Friday Walk the line climbing semaphore signal and trimming lamps and filling with oil.

There were just three semaphore signals in Keymer's section, the up Home, outer Home and a Distant. This latter signal was over a mile from the box. The lad walked to these signals carrying a can of oil, wicks and a box of matches. The oil lamps burnt twenty four hours a day, and had to be refilled on a weekly basis. If the signal lad was at the top of the ladder when an express train passed him below, the ground would shake. This in turn would shake the signal post and the lad had to hang on for dear life! Now the scene has changed. British Rail have modernised the area, the signal boxes and signal men. Station houses and semaphore signals have gone. Even the signal box at Brighton is now controlled from a building at Three Bridges, which doesn't even look like a signal box.

THE LOCOMOTIVE DEPARTMENT

During my six months in the signal box I applied for a transfer to the above Department, as an engine cleaner. This request was duly granted but it was not to Brighton I was sent. Three Bridges, some twenty two miles away was my posting. I started there on the 19th of May 1941. Ray Round also came from Brighton and started a week behind me. He later, in B.R steam days, became heavy weight boxing champion of British Rail. At times we did clean engines but within two weeks 20 ton coal wagons started to arrive in the yard. Using spare ground they were off-loaded making a large coal dump. The cleaners had many weeks doing this task. For the first time in my working life I was doing hard and dirty work, with no washing or shower facilities in those days. My ambition should have been to be a signal man! On other occasions I was a boiler maker's mate and on various shifts I would "light-up" engines for their duties, tend to them later when they had raised steam, and attend to other engines in steam. At that time "coaling up" was carried out by hand, shovelling coal out of 12 ton trucks (trucks were wood built, wagons were steel) onto a coal stage, then up on to bunkers and tenders of engines. Helping the coal man on the 2 p.m. to l0 p.m. shift when the engine yard got busy with engines was heavy work and I was all in when I arrived home from that day's work. The cleaners received the men's rates of pay for these different tasks, no doubt by past efforts from the Unions negotiating with the management. Some men were in the N.U.R. (National Union of Railwaymen) others like me were in A.S.L.E.F. (Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen).

During one lightning rail strike one morning, I was in the station buffet with ‘juice rail drivers’ having a cup of tea, when in came an irate commuter. On seeing a coloured driver he knew, he asked "Where is your train?" The driver's answer was “A.S.L.E.F. MAN, train is in the siding”. There was no doubt about which union he was in!

The cleaners also worked on clearing the ashes and clinker made by the locos, shovelling this waste up into ash trucks. It was while doing this task, at about l0 a.m. each weekday that Stewarts Lane, London, engine men would arrive in the yard, fill up at the water crane, then on to the disposal pit, clean the fire etc., then I would ride on the footplate to the other side of the shed to the turntable and help the fireman turn the engine around, this was before the tables were vacuum fitted. The driver balanced the engine on the turntable, and then it was pushed around by hand. If it was a "King Arthur" N.15 Class 4-6-0 with a six wheel tender which weighed approximately 135 tons balance was critical. I can also well remember No. 795 Sir Dinadin in MaunselI green paint work, lined out looking immaculate, coming off the table. However once the locos went into the workshops for overhaul that was the end of them looking smart, as they were given a coat of wartime black and never looked quite the same locos, until they visited the shops again, well after the end of 1939-45 hostilities.

FIRST TIME ON THE ROAD

July 1941. I had my first firing turn, when a special came up out of the blue. A horse box had arrived at Three Bridges on the back of a passenger train from Tunbridge Wells West. It had to be taken to Haywards Heath cattle market. I was cleaning engines at the time, and passed fireman Doug Bates was on shed duties with his driver. The running foreman told us to get a ‘U1’ Class 2-6-0 ready for the "Road", the number of the engine was 1907, still looking smart in Maunsell green. Doug and I worked the special with the one horse box and brake van. The engine and tender were longer than the train. On the Southern Railway passed firemen were senior men who had passed the drivers' exams and were rostered on the duty board as drivers when the work was available, and cleaners became acting firemen. Once or twice in a year all engine sheds which had vacancies for drivers and fireman advertised on all shed notice boards through the Southern. If a man applied to the engine shed of his choice, he would only get the position in order of seniority, there was no jumping the queue, a man's starting date as an engine cleaner was on record and once he became a driver or fireman he was appointed as such, and then to passing the medical was the next worry colour blindness, or weak sight were all causes for failure. Eighteen months from the day I started as a cleaner I had what was known as the fireman's first rate of pay. After one year of firing turns I received 9s 6d a day (48p). If a cleaner with this rate went back to cleaning engines (as I did) he would still get the fireman's rate. If the cleaners thought their rate of pay low, it is interesting to note that the conscripted private soldier received 12 pence a day (about 6p), incredible, but nevertheless true!

ENGINEERS WORK TRAINS

Saturday night – Sunday morning were usually the times of the week for trains from Three Bridges. On such a night, after the last passenger rains had gone to their destinations, I was rostered with passed fireman Charlie Doyle. What a character! Leaving the "up" side yard with a train of materials and work gangs for Redhill Tunnel and going out on to the "up" slow line, we then crossed over to the "up" fast line. The driver now proceeded to get the train moving with momentum. The green aspects of the electric signals showed up in the dark night, and could be seen one after the other for miles ahead to Gatwick Racecourse (now the airport). Charlie suddenly took hold of me in the ballroom dance position and we waltzed around the cab of the C2X Class 0-6-0 to the beat of the exhaust from the chimney! In spite of the dark war years, with certain drivers the firemen could have a good laugh and an excellent comradeship was established. Black out sheets were fitted between engine and tender, these also had side sheets. Tank engines just had the side sheets: Certainly on tender engines when the fire hole door was opened, the glare from the fire would shine up into the night sky like a search light, making a good bombing target. Blackout sheets prevented this penetrating glare. It also had the added effect of keeping the crews warm in winter, especially when running tender first, but in the summer they were hot to work under. During the day the sheets were rolled up and tied to the underside of the cab roof on tank engines side sheets were on rings, so were drawn back.

ENGINEERS POSSESSION

On another Saturday night works train, Clayton Tunnel was "Under Engineer's Possession". I was with passed fireman Len Edwards, again on a C.2.X Class. We were standing just outside the south end of the tunnel. The gangs of men were working on the "up" line, on the same side as the works train. My driver said to me "Right lad, take the billycan and fill it with water for a brew up, there is a tap halfway into the tunnel". On my arrival at the halfway mark, surprise, no tap! Gangers at work there told me the tap was at the mouth of the tunnel, north end. What a walk that was, just over three miles to the water tap and back to the works train. The "down" line was open for single line working and a goods train passed me by on the walk back to the works train. The noise from the distant rumble of the goods, deafening when it passed me, and the steam and smoke, had to be heard and seen to be believed in the confines of the black tunnel, but it was worth the effort for a cup of tea during a long night. It would have been easier if the can had been filled up at Three Bridges but then, nobody is perfect!

WHERE WAS THE DRIVER?

One summer day, working on an E.4 Class 0-6-0T with a passenger train from Horsham, then on to the Christ Hospital single line to Guildford, the name of the driver escapes me; I had been shovelling coal into the firebox. Having finished this task, I applied the injector for the water level. When that was singing away, I looked over to where the driver should be. I found to my disbelief he was not at the controls of his locomotive. The forward gear lever was notched up and the regulator to the steam valve in the dome was open. I wondered where the hell he had gone! The train was travelling at between 40 and 50 miles per hour. I looked out of the cab on the driver's side. There he was on the running plate, by the leading wheel splasher! What was he doing? Why looking under the boiler at the Stephenson's valve gear in motion. My driver had walked along the running plate which on the EA Class is about four inches Wide at the bottom of the side tank, not much of a foothold. There is a hand rail on the top of the side tank, but it is still like walking a tightrope on an engine at speed. Perhaps the driver had heard a knock coming from the motions, I never did find out. If he had fallen off it would have ruined the timetable for the rest of the day! Referring to my old rule book, 1 quote "unless it is single manning of cabs, no locomotive must be allowed to be in motion on a running line, unless both the driver and the fireman are on it". Though it could be argued the driver in this case was on the locomotive, even if he was not in the cab, the Locomotive Inspector would not have been amused had he known. At Guildford, waiting with the train for the guard's "right away" signal, a passenger was talking to a railwayman with a long handled hammer, and he asked him what his job was on the railway. The railwayman replied "1 am a wheel tapper, 1 tap the wheel and it goes 'clang"'. The passenger then asked "What happens when the wheels don't go 'clang'?" The wheel tapper's reply - "Then I know the train has gone!"

A SAD LOSS

My home at Brighton was in Ditchling Rise, which runs parallel to the London Road Viaduct. A continuation of the Rise is Argyle Road. At twenty past midday on May 25th 1941, a bomb literally bounced in the road there. (I remember seeing the groove it left). It then went through a house (it stands today), and exploded upwards under two arch spans of the viaduct, destroying them, leaving the "up" and “down" lines to and from Lewes suspended across the space that was created. Four bombs dropped the other side of the viaduct, smashing up carriages and trucks with railwaymen losing their lives. My friend Ken Hillman, who had been a messenger in London at the same time as me, was now a boiler maker's apprentice in the locomotive works. On hearing the whistling, falling bombs, he dived for cover. Simultaneously at the school, almost under the arches, Ken's mother on hearing the bombs falling dashed into the school yard to usher the children there to safety. Sadly, Mrs Hillman died later in hospital from the blast caused by the five bombs exploding in close proximity.

The damaged arches had a temporary steel structure and it was not long before the trains were running again over the viaduct under speed restriction. Later, in October 1943, the damaged arches were as good as new having been repaired. I worked on a 'K'. Class 2-6-0 mogul taking a works train to the viaduct from Three Bridges on one occasion.

BRIGHTON LOCOMOTIVE WORKSHOPS

After the incendiary bombing of London Bridge Station, the offices transferred to Waterloo Station. Lucky for the staff the building was bombed during the night, but all the equipment, files and invoices etc. were all destroyed. What had been the old London Brighton and South Coast Railway Hotel was razed to the ground and never rebuilt. My messenger friend Ken Hillman stayed on at Waterloo for a year, and then transferred to Brighton Loco Works, he became an apprentice boiler maker and after five years became a boiler maker. Now and then on the way home from Three Bridges sheds, I would call in at the works to see my old mate at work. Often he would be using an air powered riveting gun on a boiler. The noise would be deafening" and even worse if he was working on the plating connecting the boiler with the smoke box inside the door opening. In the wartime years the boiler makers did not wear ear protection pads, they had not been thought about in this country, so the noise echoed throughout the works causing great discomfort for all the men. Consequently many a man had problems with deafness in later years. The Health and Safety Act was not thought about in those days. My great friend J. Quinliven, popularly known as "Mad Jack" had left the works in the 1930s. He was a gentle giant of a man, a weight lifting enthusiast. One true story of him when rebuilding a locomotive, for he was a fitter, he would offer up (lift) a hydraulic buffer to the buffer beam. hold it there whilst fellow fitters fitted the bolts and the nuts, securing the buffer to the beam, the weight upwards of two hundredweight. No wonder he was named "Mad Jack". All the fitters would use the overhead crane, but Jack did not like to wait about for the availability of the crane.

RAIL TO TUNBRIDGE WELLS

Now it was June 1942, and as an acting fireman this particular morning I was booked on the 5 :20am "goods" from East Grinstead to Tunbridge Wells West. After "preparing" an E.5 Class 0-6-0T for the "road", I hooked the engines on to a C.2.X Class 0-6-0. This engine was hooked to an I.l.X 4-4-2T, which in turn was hooked up to an 1.3 Class 4-4-2T. The four coupled locos now crossed the London & Brighton main lines for the single line to Rowfant, with the single line staff (key) carried by the last engine in the rear. On arrival here the staff was exchanged for one marked Rowfant East Grinstead. Once here the staff was handed to the signal man. Stopping at the station platform, all the engines were now uncoupled. The E.5 trundled over to the Goods Yard, with the 13 going on light engine to Forest Row to work a London passenger train. The I.l.X went down the incline to the low level station to work a passenger train to Brighton via Sheffield park (Bluebell Line) while the C.2.X would now work a "Goods" to Oxted. My mate and I now worked the "Goods" to Forest Row. Passing the train for London in the "up" platform, we shunted the yard here. Next down the line would be Hartfield, Witham and Groombridge. Leaving Forest Row behind us the sun was rising in the east, on my side of the cab. The morning dew was slowly dispersing at the start of a lovely summer's day. The scent from the countryside was like a wonderful perfume that filled the air all around, from the trees, terns and flowers plus the earth and grass. The single line now was mostly down gradient. The section between East Grinstead and Forest Row was 1 in 70. The engine was lightly worked with about ten trucks in tow I shall always remember the fragrance from the picturesque Sussex countryside on this early morning. "Goods" we passed playful hares boxing one another, the colourful plumage of the cock pheasants, and all kinds of birds singing their happy song in the trees and hedgerows, and flying happily on the wing. The scene, trundling along at 25mph was tranquillity itself, and a far cry from the death and destruction not many miles away across the Channel, or indeed the bombing here in England at that time, caused by man's inhumanity to man during the war, or in the so-called peace later declared, On arrival at the West Station, after uncoupling in the Goods Yard it was over to the engine sheds where I cleaned the fire ash pan and smoke box. My mate inspected the Stephenson motions etc. for defects, and any other parts that needed to go into the repair book. After taking on coal and water it was over to the "table", where we turned her around and left her on one of the shed roads, screwed the hand brake on, opened the steam cocks, shut off the Westinghouse brake pump, and put the reversing lever in mid-gear. The running foreman gave us an Ll.X Class No 2602 to work a passenger train back to the Bridges. Walking over to the loco my mate, on seeing the wartime black painted machine said to me "What a picture of misery!" "Yes", I said, "She is". Once the engines went into the shops they lost the smart coat of Malachite green and the yellow lined letters of "Southern" on passenger engines. On the "working" back to the Bridges we usually had a Bridges engine No 2600, which then was still in pre-war colours. Of course this picturesque branch line was closed back in the 1960's under the Beeching axe. I did volunteer work in 1970 for a year on the-Bluebell, where there is an abundance of steam and pleasant Sussex countryside to see from the carriage window.

A MIDNIGHT SWIM

Most of the early turns of duty or rosters for drivers and firemen at Three Bridges started from 3.0 a.m. onwards. The first stopping train from Brighton to the Bridges left at 5:48am. and not in time for the early rosters. So I would catch the 11: 15pm van train for London Bridge, which stopped at the Bridges, or I would get the 12:40am Three Bridges "Goods" from the top yard. It was a Three Bridges rostered working. I had worked it a few times; the engine was usually a 'K' Class. I travelled many times with an old school chum's father, "Goods" guard Chapman. The brake vans were often six wheelers and at times were bone shakers, for after passing Clayton Tunnel, the train would get a move on, and then the van would vibrate and shake the life out of me. How the guards put up with that vibration on their daily runs I never did ask them. Not long after the bombing of the Viaduct, the family moved to Hove, but not far from the Brighton running sheds. To reach the "top yard" now, I would take a shortcut and walk through the sheds to the North East corner, then out into the open, walk over New England Bridge, walk across some sidings and the electrified main line. I was now by the brake van of' the goods train. I had gone this way two weeks earlier using the light of the moon, in Dec. 1942, to guide my way in safety. On this particular black night I made the mistake of not having a torch upon my person. I had crossed the bridge but walked on too far. I now turned to cross the sidings and main line. I lifted my foot high over what I thought was the "juice" rail and stepped over. That's when I fell into a pit full of water. With my fireman's cap on my head I can remember swimming using the breast stroke to the end of the pit, and walked up the steps leading out of the pit. I was soaked through to the skin, so I took my well sodden body back to the engine sheds where there was a furnace used for lighting up dead" engines, and over the top of the furnace sand dried out used in the loco sand boxes. In front of the opened furnace I undressed and dried out. Fortunately I did not see a soul. When my clothes had reasonably dried out I dressed and took off for the running foreman's office. From there I phoned my foreman at Three Bridges telling him of my misfortune and why I had missed the "Goods" and was not able to arrive for my roistered firing turn. Of course word soon got around my shed. Engine men asked each other if they knew the clown who took a midnight swim in the Brighton water pits on his way to work. It took quite a time for me to live that down! A number of D.1 Class 0-4-2T Stroudley engines were equipped with pumps and hose pipes for fire fighting purposes. They were stationed at various sheds on the Southern during the 1939-45 war years. Nine Elms used the water from a spare tender. If Brighton had used this method instead of a pit filled with water, I would have stayed dry on that ''wet'' night. I was not on duty when going to catch the "goods". By crossing the running line I was, in fact, breaking the roles. Employees not in the course of their duties were forbidden to cross the running line. After that ducking I took a longer route to the top yard when going for the "goods"!

A HAPPY MAN

Three Bridges running shed did not have any' D l Class allocated to the shed while I was there, but I did have one trip on the Class from Horsham to Brighton. The first journey on the "working" was an early morning van train from the Bridges to Bognor with an I.3 Class 4-4-2T, and speeding down to Faygate was driver Bungee Charman, his smiling face lighted up by the red glow from the fire hole half door opening. Looking in my direction, he shouted over, saying "Isn't this great Norm?” If ever a man enjoyed his work on the footplate of an engine, he did. On arrival at Horsham engine men from that shed would relieve us and work the train on. My driver and I waited then for a passenger train from London Bridge which was routed via West Croydon and Dorking Town, crewed by New Cross Gate men.

On this particular day at the head of the train was a D.1 Class 0-4- 2T. Changing over with the New Cross men, we filled the tanks at the water crane and worked the train to Brighton via Steyning, working back to Horsham, usually with a D.3 Class 0-4-4T. The double tracked line was known by railway men as the ''Linger''. One reason for the name I had been told was because it was the long way round from Brighton to Three Bridges. Another version was the Steyning line, linger and die on another day the engine was a Billinton BA Class 4-4-0.

This class along with the D.1 Class were m their final years before scrapping. I did not see them again. Maunsell had some of the B.4 Class rebuilt to B.4X. There was another sad day, it happened not long before the closure of the Linger in 1966. A "goods" bound for Horsham and powered by a diesel engine ran by the Home signal at Danger for Itchingfield junction and ploughed through a "goods" on the Mid-Sussex line. Sadly the crew on the diesel lost their lives. Of interest to me, later in the 1970s I met the Horsham man who was in the brake van on the back of the Chichester bound train, on that fateful night, goods guard Foster.

A ROUGH TRIP

An engine had failed at Three Bridges Station when working a special from Addison Road, Kensington to Newhaven. I was cleaning engines at the time: Passed fireman Fred Elliott and I were given orders by Charlie Miller, the running foreman, to do a rush job preparing a Q Class 0-6-0 for the road and take the train at the station to its destination. The driver drove the engine to the coal stage, willing hands helped us to place the coal into the firebox, but too many large lumps were hastily fed into the box which, in turn did not burn through quick enough, for on the rising incline to Balcombe signal box steam pressure dropped down, showing only 80 psi on the steam pressure gauge, but fortunately the Q had a powerful air ejector to create the vacuum in the train pipe, otherwise the brakes would have automatically been applied when low on steam. By using the dart (like an 8 ft. long house poker) and lifting the packed coal this allowed more primary air to reach the grate area and the fire. Entering the tunnel, the Q was slowly "coming round" and "steaming" at last.

A STRANGE MAN

As a Cleaner on the 7.30 a.m. to 3.30 p.m. shift once or twice I would go home on the Brighton portion of the Bognor Vans from London Bridge. The enginemen were from Three Bridges. I would ask the driver for his permission to ride in the cab and perhaps learn the skills of driving and firing. The engine was usually a Class K, Brighton built mogul, on this particular day the fireman was a senior cleaner (known on the Southern as an acting fireman) nick-named “Split” and he was a good fireman. Three Bridges was a sub depot of Horsham, so on occasions the Locomotive Superintendent would call. But for reasons I never knew Cleaner Split had a hatred for the ‘Super’. Sometime later all of young cleaners were reading the notice board which had vacancies for drivers and firemen all over the Southern Railway system. Cleaner Split was also reading the vacancy sheet, and then saying to his fellow cleaners. “I am going to apply for a fireman” in chorus we all exclaimed, “where are you going” so he just said “anywhere.” Later he got his fireman’s appointment. Drivers and fireman and cleaners soon knew where and what running shed Split was going too, yes! It was Horsham. Just about the last place on earth he wanted to go. Why he did not apply for Redhill or Norwood was strange, for it was easy distance from his home at Brighton and important for Split he would not be anywhere near his mentor. He did not stay long at Horsham. The last I heard of Split, he was working at Shoreham-by-Sea gas works. How he was allowed to leave the railway during the war to me a mystery for Split was in a Reserved Occupation. I passed for the Navy, and was told I had to stay where I was.

L.B.S.C.R. ATLANTIC AT THE BRIDGES

During 1941 a number of engines were stored on a siding by the down Brighton main line, just north of Three Bridges station. One of them was a Brighton Atlantic she was placed back in traffic and came into the engine sheds nearby to be serviced and cleaned. The engines we cleaners normally cleaned were E1, E4, E5, I1X, I3 and C2X, which were allocated to the shed at this time. I do not know the number or the name of the Atlantic now. The shed foreman gave myself and fellow cleaners the task to clean the engine. I remember I was on top of the boiler with cleaning rags and oil the boiler seemed to be endless in length to what I had been used too and it was the first and the last time in my 2 ½ years at the Bridges that an Atlantic came into the shed. Later in 1946 when on loan to Stewarts Lane as a fireman I worked on of the Atlantic’s and wished I had worked them more often.

One of the Passed Fireman at the Bridges was appointed a driver at Horsham he lived in the town, his son was a cleaner at the engine sheds, he was appointed fireman at Newhaven. I often met up with him at the Lane with his driver. He would come in on an Atlantic having worked to Victoria on a Boat Train, no doubt Newhaven running sheds at least three Atlantic stabled there in those days. The class were looking smart in Bullied’s ‘Malachite Green’ with ‘Southern’ on the tender sides. Today when I see a train with no locomotive (steam) on the front, I do not turn my head at all to look but a loco on the front, out would come my camera.

THE SPARKS FLY

I was working the 5: 18am Sunday morning paper train from Victoria to Brighton one summer, with Driver Hodgeson, on a Class Q1, 0-6-0. The train was at speed near Horley, and the vacuum gauge pointer was wavering up and down. I looked out of the cab towards the Guard's van. The guard was frantically waving us down to stop, as a sheet of flarme and flying sparks were coming from one of the vans. I shouted to my driver to drop the "handle", which he promptly did. The guard had been applying the emergency brakes and his van, but It did not stop the train. It was by the odd reading on the vacuum gauge that I realised something was wrong. My mate intent on watching the "road" ahead, did not notice the vacuum gauge s odd behaviour at the time.

When the train came to a halt, driver, guard and fireman ran to the van which was causing the trouble. One of the brake hangers had broken loose and was now fouling the "juice" rail.

I ran to the brake van where the guard said I would find a long wooden shaft handle. It was either my mate or the guard who cleared the obstruction. I do remember though, the fireman stood well back from the flames and showering sparks - I was no electrician!

With the brake hanger now secured, the van continued on its way to the next stop, Three Bridges (a paradise for firemen, I should never have left), arriving at Brighton twenty minutes late. After the engine had been on the table it now had to work back to Victoria via Lewes and Edenbridge Town with a passenger train.

SHUNTlNG

It was hard on a driver if he failed his medical, like the eyesight test on his appointment, or if in later years he failed Re would now most likely be roistered on shed duties if the engine yard was a large one or he would be condemned to the Marshalling or Goods yard shunting engine. As luck would have it, I did not do much shunting work. In my early firing days at Three Bridges, I, like other passed cleaners, did work now and then on the "up" and "down" sidings on E.1 Class 0-6-0T. I had one day in the Poole goods yard shunter with an M.7 Class. The driver and I had shunted up and down for more than seven hours. At the end of the day my driver said to me "That's what I call perpetual b****y motion". I also had a day on the Bournemouth goods yard shunter with a G. 6 Class 0-6-0T. The fireman had to stop the engine, and the only brake was on his side of the cab, which was a ball bearing hand brake. Seven hours or more of screwing the hand brake on and off was not my idea of happiness, so I was pleased never to see Bournemouth goods yard ever again. Fireman's verbal instructions to driver decoded from shunter's hand signals in daylight and darkness, if shunter is on fireman's side:

SPECIAL TRAINS AMBULANCE

My driver this day was a Top Link engineman, before the 1945 hostilties he must have worked on the Bournemouth to Brighton service, this was cancelled during war time although Brighton still worked the service in the morning and return later that day, with a Class S15, it was tender first to Blandford on the Somerset and Dorest. Arriving there we coupled to an ambulance train off the L.M.S. injured sailors where en-route to Haslar Naval hospital in Gosport, Hampshire, these trains often had fourteen coaches on behind the tender, our load was no exception. I knew after St Denys the road was like a switch back, though I had never worked over this road, but I often been a passenger going to my family home in Hove. Now the locomotive was working hard with the heavy train on the gradient to Brisledon with the reserve curves, on and over the River Hamble to Fareham, Cosham, taking the right hand semaphore signal for the line to the next junction from Havant and on to Fratton Station where we stopped at the platform. My driver was not sure of the signals for the line ahead, so he sent me over to the ‘Box’ crossing the lines, halfway there the signalman was waving his arms and shouting “Alright to proceed” no doubt my mate knew the road to Brighton, but I did wonder if ever driven a train to Portsmouth, anyway I didn’t ask. We arrived at Portsmouth Harbour alright. Here the sailors embarked for the short sea crossing over the Solent to Haslar Naval Hospital. Once our train was taken to the sidings by the station pilot. It was tender first to Fratton engine sheds, where we left our steed. Now home on the cushions, my mate to Bournemouth, myself off to Hove for a one night stay.

SENTINEL STEAM RAILCAR No.6

While still school boys with my friends we would go training spotting to Hove as well as Brighton, about one hundred yards east of Hove station a fence and on a level with the railway lines was Hove ‘A’ signal box, beyond that were the sidings for the goods yard. From our advantage point we could see the yard shunting engine at work which usually was a Class E1 0-6-0. But what was most interesting was to see a Sentinel Steam Railcar go by on its way to and from the Dyke Railway. This line closed in 1938. I am not surprised that it did so, for on reaching the Dyke Station, passengers had to walk half a mile or more to the Dyke Hotel, which I am told is the second highest point on the Southdown’s, as Ditchling Beacon is the highest. The climb from the Dyke station is steeper to the hotel than the 1 in 40 Dyke Railways. Today people arrive by bus, car or walk to view the five or six counties that be seen on a clear day, plus the fact it is a haven for Para gliders.

During my firing days at Bournemouth locos sheds, I often worked with Driver Fred Dunstan, who during his firing days at Brighton often worked the Sentinel Steam Railcar No.6. however these railcars were not that successful climbing the 1 in 40 gradient, for once it left the south coastline the climb was constant to the Dyke station. Unlike the Sentinel steam lorry built at their Shrewsbury works.

AT BOURNEMOUTH SHED

The first gang I was in was the Poole Quay shunter. On early turn the driver and fireman prepared an old Adams B.4 Class 0-4-0T for the road. Going off shed it was light engine to Poole yard, then couple up to five or more trucks, with two shunters. We trundled along to the Quay side with one shunter in front, one at the back of the train, with red flags at the ready to stop traffic .from running into the train. The railway lines went in a half circle at cross-roads and T -junctions to get around them. In some places the train ran on the right hand side of the street. It was on this side, when stopping at the Workman's Cafe, the railwaymen would all pile in to the cafe for refreshment, and vans and lorries would park behind the train, with their drivers also in the cafe, This is now, of course, just a memory for those who knew Poole the way it was. At my first lodgings, every day for my packed lunch I was given plain cheese sandwiches. Unfortunately I never liked cheese, so each day at break I would wipe the shovel clean, place the sandwiches thereon, and by resting the shovel on the fire hole ring, I would have toasted Cheese. It was more edible. Later, when in another gang, arriving in Poole yard on a "goods" with a Kl 0 Class 4-4-0, we had shunted the trucks and were at rest having our lunch. My driver was frying some chops using the shovel on the fire hole ring, when the shunter came up and asked him to move the trucks: up a few yards- Of course, my mate forgot about his fry up, opened the regulator, and the force from the exhaust steam up through the blast pipe sucked his chops into the firebox. They were burnt to a cinder and lost. I remember the September sky that day was blue, but the language on the footplate was even bluer!

GOODS IN HAMPSHIRE & DOREST

When I was appointed a fireman at Bournemouth, passenger workings were by far more numerous than freight workings. However one roster I did look forward too was a goods from Feltham Middlesex, marshalling yards. After signing on, the crews had to look at notice board applying to this particular working, as it was a short walk to the station and a ride on the cushions to Eastleigh. Here the goods stopped on the down line, we relieved the Eastleigh crew, the engine was usuall a war department 2-8-0. I found this class to be excellent, free steam with plenty of space in the cab. At times for various reasons there was a shortage of crews,more than often I travelled to Eastleigh alone, so the Eastleigh driver was on overtime. The lenght of the train could be fifty, sixty or more wagons. The destination was Poole sidings. These 2-8-0's had a peculiar fault, one I had never met before. If the speed reached 35 to 40 m.p.h. The linkage between engine and tender would vibrate and shake the life out of the crew, not a very pleasant experience, with the speed reduce it would cease, Speed meters were to come later, but thesetrains were timed to clear the expresses from Waterloo, so we had to motor.

Most of the lines on the Bournemouth were one down one up except between St Deny's to Northian, Southampton to Redbridge and the two down and two up at Pokesdown, so there was little chance of being overtaken the traffic just piled up behind us. We tried to keep out of the way of the fast trains and arrive at Poole sidings on schedule. After the goods was propelled into the yard, it was tender first to Bournemouth where I cleaned out the smokebox, cleaned the fire etc. The Eastleigh man returned home on the cushions.

THE NELSONS

The next gang up on the afternoon (2:00pm - 10:00pm or 4:00pm - 12:00am) had the main line engines on the roster for "disposing" or putting away when the "top link" engine men arrived at Central Station from Waterloo. In those days it was usually a Lord Nelson Class 4-6-0 and when they left the footplate my driver and I got on taking the front portion of the train to Bournemouth West, the rear six coaches going to Weymouth. After arrival at "West" station when the train was empty it was then propelled up the incline to the carriage Sheds. After. this movement it was light engine to the Central sheds where the fire, ash pans and smoke box were cleaned (one smoke box took me an hour to clean), then we were taking on coal, filling water tanks, then onto the turntable, and stabling the loco for the night. On early turn the engines were prepared for the "top link" men who had their own Nelson in those days, the driver oiling up all the necessary parts, the fireman slowly building up a boxful of fire and raising steam, then shovelling the coal forward from the back of the tender. The job I disliked was filling up the sand boxes. Buckets of non-slip fine sand had to be lifted up onto the running plate and poured into the sand boxes, every grain kept away from the moving parts, but the trains did not stop because of ice or leaves on the line. Then it was up to the "dummy" (ground signal), waiting for the signal man to pull it off, light to Bournemouth West. Once there, back on to the carriages and couple up. Leaving Bournemouth West with six carriages for Central Station, the Station pilot was waiting for a further six carriages which had come from Weymouth. On arrival were now pushed or propelled onto the waiting six carriages forming a twelve coach train for Waterloo. "Top link" men now took over from my mate and me, a round trip of 232 miles in front of them. After a given number of miles they were on mileage pay. This was the link to be in, but it took a few years for a fireman to reach and even longer for a driver.

ROUGH CIDER

I can well recall my first trip to Weymouth with Sam Baker on a Nelson. It was a "top link" working at Central Station. Bournemouth men would relieve Nine Elms men and take the train onto Weymouth. After arrival at the terminus it was light engine to the G.W.R. sheds to turn the loco on the table. Then it was tender first to a siding outside of the terminus and then wait until train time. On the other side of a low parapet wall and across the road was a "Strong" public house, temptation for a quick drink on a hot summer day, but I made the mistake of having a pint of West Country rough cider. Leaving Weymouth behind us, on the climb to Bincombe tunnel I was suffering from a light head, shovelling coal into the 10'6" firebox as if I were a robot under automatic control. By the time the train reached Dorchester I had worked it off by perspiring from my labours.

Passing the "up" station platform on our left going into the curve of the line, the driver stopped when the guard showed his red flag. When the points were set, on the now straight section of the line the guard waved us back with his green flag and the driver propelled the train into Dorchester's one platform terminus. The downside platform was on the other side of the line. Leaving Dorchester with the semi-fast train to Waterloo, on reaching Bournemouth Central we were relieved by Nine Elms men. That was the first and last time I had rough cider, as it was rough on me! I have been a "mild" man ever since! Now trains do not reverse it has a new through road at the station.

A NEAR MISS

On a special train from West Moors petrol dump in the New Forest the driver was Ted Vigar, the engine was a 4-4-0 tender K10 Class, with a load of petrol tanks bound for Southampton Docks. When we apssed Ringwood: the loco working hard up a bank, and with the shovel in my hands, my head down and backside up, I was hard at work keeping up steam pressure, when suddenly, above the beat of the exhaust, at the engine's chimney, there was the sound like machine-gun fire. The driver and I gave one another a blank stare and looked out of the cab side towards the guard's van, and in the distance a plane was fast disappearing. It was the German Luftwaffe. Fortunately the pilot had not been on target and did not return to the highly inflammable petrol train, so we were able to proceed to the docks in safety. Later that year on the other side of the English Channel the RAF. dive bombed all trains, blowing them up, locomotives also. I had seen these air strikes on Pathe News at the local cinema. The face of good fortune had smiled on the Bournemouth guard and engine men that day.

SOUTHAMPTON DOCKS

"Queens" was in dock, having arrived from America with thousands of troops. My driver and I were now in a siding behind other engines waiting for a train at the dockside. It took some hours for the Yanks to disembark. Later one of the dock shunting engines had brought empty carriage stock in the platform. At last it was our time to back onto the train and couple up, which on the Western section was carried out by the fireman. While the Train was being loaded there was refreshment for the Yanks on the platform of coffee and doughnuts, and we left the docks at approximately 3:30pm for Basingstoke. On arrival at this station my driver and I were relieved by engine men from Reading shed.

The Bournemouth men now expected to have a ride home on the cushions as originally stated on the "special notices", but the Basingstoke running foreman had other plans for Henry and Denty. They now had to report to him at the engine sheds, the message having been passed on by the Reading engine men. On our arrival at the sheds the foreman informed us that the T .14 Class 4-6-0 on one of the shed roads was ours, and we were to wait for an ambulance train due off the G.W.R. via Reading, with wounded Yanks returning to the U.S.A. on the "Queen" now at Southampton Docks. Basingstoke had no available crews to relieve us, and not even control knew what time the train was due. My mate and I were in for a long and boring wait, and as it turned out, it was for eight hours. The ambulance train finally arrived at the station at about 1:30am. Ten minutes later I had coupled up, the guard ,gave his green light hand signal and we were "right away". These ambulance trains had sixteen coaches to pull.' On the climb to Litchfield Tunnel, the old "Paddle box" with the four cylinders working hard, struggled with the heavy load hooked en behind the tender, the m.p.h. no faster than a heavy "goods" working flat out up the bank. Fortunately for the fireman the "paddle box" steamed well enough while it was being hammered up to Litchfield Tunnel. Then it was a downhill run past Micheldever, Winchester, and on to Southampton, running in alongside the dockside platform, stopping here at approximately 2:30am. The T.14 arrived on the disposal pit at Bournemouth sheds at about 3:30am. I screwed down the hand brake, and my driver and I just about fell off of the footplate. We signed off duty at 3:30am, twenty hours after signing on. It was indeed a hard day’s night! I can well remember the time I was off duty, which was eight hours, and then I had a shovel in my hands once again!

THE L.M.S.R.

During the time I was at Bournemouth the Branksome shed L.M.S.R. engines were stabled at my shed. One of the Southern's cleaners was on loan to the L.M. S. as a fireman for a long spell, working to Bath Green Park and back to Bournemouth West on a 2P Class 4-4-0. These engines were built for the old Somerset and Dorset Railway and had 7’01/2” driving wheels. They often passed me at Poole Yard when I was on a "goods" waiting to leave the yard after the Bath train had cleared the section of the line. To my surprise I was on loan to the L.M.S. for one day. The engine was a 4F Class 0-6-0. Going off shed, it was light engine to Poole Yard, and then we were working a "goods" to Evereach Junction, arriving at Bailey Gate, shunting the yard, then on to Blandford, and bumped the trucks about here. When the goods train was sorted we then waited in the "up" platform for a train from Bath to arrive on the next line. My driver and I changed over with the crew on a Black Five 4-6-0, taking the passenger train on to Bournemouth West. Great locomotives, those Stainier designed machines. I would have liked to have worked on them more often, over Southern rails.

PUSH AND PULL

No.3 Link was the "Push and Pull". Crews had their own engine (except on shed days), early turn engine men sharing a loco with the late turn men. The firemen kept the cabs immaculate with polished brass and copper pipes gleaming, and this was during the war years when locos were not as clean as they might have been, though at Bournemouth shed they had young lady cleaners who did a grand job. I was not yet in the "Push and Pull" gang, though for some reason or other I had plenty of opportunities to work in it. On early turn the crews got a Drummond 60 ton M.7 Class 0-4-4T ready for duty. Going off shed it was light engine bunker first to Bournemouth West, then back on to a push and pull set, hook up with the screw couplings vacuum pipe, compressed air pipes and connect the plugs for the electric bell (bell code between engine men). Also, if it was winter service, the steam heat pipe had to be connected. The fireman did not have much room to move between engine and carriage. It was just as well most firemen were slim enough to get out of the maze of pipes after connecting and coupling up. The vacuum and compressed air gauges were tested for correct readings. If all was in order, the train was now ready for the "road". When the time came to depart, it was off all stations to Brockenhurst Old South Western, main line. When working the train back to Bournemouth from Brockenhurst the driver would now go to the guard's van where there was a driving compartment complete with vacuum brake, whistle and a regulator handle. This handle was connected through the compressed air pipes to the steam regulator on the engine, which the engine men connected up by a movable steel rod secured by a large pin and chain. The compressed air was created by a Westinghouse pump on the running plate. A ring on the bell from the driver, acknowledged by the fireman, meant "right away". The driver now opened the regulator handle in his driving compartment, and the fireman had to be ready in case the regulator in the engine cab opened too wide.

Inevitably, this would happen, causing the engine driving wheels to slip. If the fireman opened the sand lever, spraying sand onto the rails while the driving wheels were slipping, there was always the risk of bending the coupling rods. The fireman, however, could not close the steam regulator because of the compressed air. To get over this difficulty, I, like other firemen, took out the pin connecting the rod to the steam regulator and worked the engine as though I were the driver. In any case, the fireman had to notch up the reversing lever for valve cut off.

The driver had control of the train with the vacuum brake in his compartment up front. The brake handle on the engine was placed in the running position and the small jet valve opened, maintaining 21 inches of vacuum reading on the gauge. Once the train was on its way it could be all stations to Christchurch via Ringwood. I was now in my element as the train sped along towards Ringwood, quite a few miles away. A ring on the bell from the driver meant shut off steam. On one occasion I kept the regulator open for a few more miles. The train was moving at high speed, the driver up front must have been quite happy, and did not check the speed of the train. At Ringwood though, we had to wait fifteen minutes before the guard gave his "right away" signal. Margaret Lockwood, the film and stage actress, lived in the Ringwood area, and was often on the "Push and Pull", changing at Brockenhurst to or from Waterloo. Firemen had to look out for the locomotive inspector who could be standing waiting at any station. If the steam regulator handle was not connected to the pin and chain, on seeing him waiting at the station the fireman had to couple the pin and chain in double quick time, otherwise the gentleman in the bowler hat would have you in the office later and give a lecture in chapter and verse about engine men's rules as contained in the railwayman's Bible, "The Rule Book".

WORKING AN L.B.S.C.R. ENGINE

One afternoon in the summer of 1944, a train from Waterloo came into the platform road at Bournemouth Central. I was with driver Fred Billet a gentleman and a good engineman. The train stopped by us and we relieved the crew from Nine Elms sheds and we climb up into the cab, to take the train to Weymouth, stopping at all stations. The engine was a Class N15X, No. 2333, Remembrance. I was pleased to be working an old L.B.S.C.Rly. Locomotive again, for my original shed had been one of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway, now Southern Railway. On the way up to Branksome I noticed a large hole in the wooden floor by my feet, I could see the right hand rear driving wheel with the coupling rod, the cab was swaying to the left, then the right, quite a rough ride, I thought then, she needs to go to the shops for overall, anyway I forgot about it, and got with the shovelling coal into the firebox. At Weymouth, the station pilot took our now empty train to the carriage sidings. We now went tender first to the G.W.R. engine sheds, once on the ash-pit, I cleaned out the smoke box, then I noticed four fire tubes were leaking, I called my mate to look, he made a note in his repair book. I now cleaned the fire, throwing out the clinker, there were two tubes leaking just above the brick arch. On seeing this Fred rang the Running Foreman at Bournemouth Running Sheds telling him No. 2333 would not make it to Waterloo with twelve on. Also we would need a banker at Poole Town even with six coaches for Pokesdown Bank. After servicing and turning the loco, it was back to Weymouth station to work the train back to Bournemouth. At Poole, a Class M7 came on the rear and banked us up to Branksome. At Central station, I uncoupled the engine from the coaches, and then we took off for the engine yard. Six coaches from Bournemouth West were now propelled forward onto the six coaches by the station pilot. A Class V ‘Schools’ now took over the head of the train for Waterloo. Later in the week No.2333 was coupled to an engine and brake van destination Eastleigh workshops.

LORD NELSON LOCO No. 850

Like many railway enthusiasts, I am particularly pleased to see No. 850 is working again over the railway lines of this country. During my time at Bournemouth No. 850 was allocated to the running sheds, when I was in the preparation and disposal gang, I worked on this engine many times.

It was near Xmas 1944 that I worked on Lord Nelson it was a number 2 link working, from Bournemouth West to Eastleigh and it was all station stopping train. Having come off at Eastleigh, it was tender first to the engine yard; No. 850 was booked for an overhaul at the workshops. I remember that particular day well. The Running Foreman allocated my driver a Class H15, then it was tender first to Southampton Terminus, here we coupled up to the night mail ex-Waterloo. The train was long, and well loaded, until we reached the top of the incline at Pokesdown. I did not stop shovelling, in my endeavours to maintain the necessary P.S.I. for this fast working to Weymouth, and the ‘Pep-pipe’ was not working properly to keep the coal dust at bay. So I was relieved, when I was relieved by Dorchester men. The fireman was a bit of a wag, saying to me “You look like you have been in the black hole Calcutta.” His driver’s comment was no better “You look like you are off to the Chimney Sweeps Xmas ball.” Looking in the mirror later I could see why they had a laugh. By the time the Dorchester men arrived back to their home shed, the fireman no doubt looked like a coal miner on his way to the pit head baths. No, I didn’t tell him about the Pep Pipe and the dusty coal.

THE AIRWAYS SPECIALS

In the 1930s the Southern ran Airway special trains from Victoria to Poole Harbour of Southampton Docks and from there to Victoria or waterloo for flying boats passengers. This service continued during the 193 – 45 war and for a time in the post war years. Short Brothers built the Sunderland flying boats, and when these graceful machines touched down on water and came to rest at anchor, the passengers boarded motor boats for the quayside at Poole, and then they were taken by motor coach to Bournemouth West Station. Waiting here would be an engine and four or five Pullman cars, but in war time there were no car attendants to serve the needs passenger on the journey to the British Over-sea Airways Corporation Hotel at Victoria Station. Across to the hotel could be gained from where the train stopped at was platform 17. By the departure end of the station near the signal box on the countryside. No. 2 gang at Bournemouth Shed had a B.O.A.C. Airways working, and was a standby roster time of departure was only known at short notice during war time and could run A.M. or P.M.to or from Victoria.

While I was at Bournemouth the special usually ran only once a week in each direction in the week. In 1944 - 45, I was called out by a ‘call Boy’ from my lodging many times to work the B.O.A.C. Specials. When the crew booked on duty it was either a ride on the cushions to Victoria, or go tender first to Bournemouth West with a T9 Class 4-4-0 or a Stewarts Lane E1 Class or a D1 Class 4-4-0.

Leaving Bournemouth West, the Airways went on the ‘Through Road’ at the Central station on a non-stop run to Victoria, slowing down at Wimbledon station for the Stewarts Lane conductor to jump on the footplate. He was there if the Bournemouth Driver did know the road to Victoria. In these days there was no crossover at Clapham Junction from the Western to the Central Section.

From Wimbledon the Airways went via Haydon’s Road, Tooting and on to Streatham Junction spur meeting the main Brighton – Victoria line. On arrival at the terminus a Stewarts Lane fireman would be waiting, my Driver and I were now relieved from duty, we then made our way by tube to Waterloo for a ride home on the cushions.

Leaving Victoria on the Brighton down line the airways passed over the fly over at Streatham Junction for Wimbledon and on to the Western section for Bournemouth West.

It was probably the longest non-stop run on the Southern during the 1939-45 hostilities, about 116 miles. It was easy work for the fireman with a light train on a very fast train. The driver and fireman must have enjoyed the trip. I know I did.

SPECIAL TRAINS AMBULANCE

My driver this day was a Top Link engineman, before the 1945 hostilties he must have worked on the Bournemouth to Brighton service, this was cancelled during war time although Brighton still worked the service in the morning and return later that day, with a Class S15, it was tender first to Blandford on the Somerset and Dorest. Arriving there we coupled to an ambulance train off the L.M.S. injured sailors where en-route to Haslar Naval hospital in Gosport, Hampshire, these trains often had fourteen coaches on behind the tender, our load was no exception. I knew after St Denys the road was like a switch back, though I had never worked over this road, but I often been a passenger going to my family home in Hove. Now the locomotive was working hard with the heavy train on the gradient to Brisledon with the reserve curves, on and over the River Hamble to Fareham, Cosham, taking the right hand semaphore signal for the line to the next junction from Havant and on to Fratton Station where we stopped at the platform. My driver was not sure of the signals for the line ahead, so he sent me over to the ‘Box’ crossing the lines, halfway there the signalman was waving his arms and shouting “Alright to proceed” no doubt my mate knew the road to Brighton, but I did wonder if ever driven a train to Portsmouth, anyway I didn’t ask. We arrived at Portsmouth Harbour alright. Here the sailors embarked for the short sea crossing over the Solent to Haslar Naval Hospital. Once our train was taken to the sidings by the station pilot. It was tender first to Fratton engine sheds, where we left our steed. Now home on the cushions, my mate to Bournemouth, myself off to Hove for a one night stay.

A SHOVEL LOST

My next gang up the ladder to the "top link" had local "goods" and passenger workings. My regular driver was Bob Adams. On this particular day we were on an afternoon homeward bound workman's train from Wareham. The engine was a (LSWR) S11 Class 4-4-0. Waiting at the platform tor the time of departure was my girlfriend at the time, who worked in a factory nearby. She came up to the engine and had a word with my driver and myself My mate, knowing the young lady lived at f!~worthy Junction, invited her to have a ride on the footplate, which she duly accepted. Receiving the "right away" from the guard, we were off, stopping at all stations to Bournemouth. The train was rattling along, so I dared the lady to try her hand at firing with the shovel. She was anything but a shrinking violet, and coal was sent into the firebox with great skill, but alas, calamity struck (her name must have been Jane), the shovel slipped out of her hands and was lost in the heat of the fire box. Bob was a placid man., he never said a word. From the junction, using my hands, I fed lumps of coal into the firebox till we reached Poole Town., having a good box of fire now for the 1/64 Parkstone Bank ahead. Later at Bournemouth when the engine had been "put away" for the night in the engine yard, I looked for a firing shovel in the shed among the brake blocks, tubes, firebricks and other locomotive bits and pieces used for repair work. Luckily I found one, it had been battered about a bit, but now at least I had a complete set of tools to hand in at the store. The store man gave me an old fashioned look when I handed them over the counter. It saved me from a lot of embarrassing questions. Later the girl friend told me that the signal man on duty at Hamworthy box had seen her getting off the :L12.Class engine. She had been chastised by him in no uncertain manner. The signal man was her father!

CLAPPED OUT

One late afternoon on a passenger train to Eastleigh on No 563 X6 Class 4-4-0 (they were very similar to the T.3 Class), while working through the New Forest, the engine broke down". Driver Watts sent me on to Lyndhurst Road Station to arrange for assistance with the Station Master. I had a walk of approximately two miles, and I had just arrived on the platform when my train arrived. The driver had managed to-get the old Adams L.S.W.R main line engine working. She was being worked back to Eastleigh to go into the "shops" for overhaul. It was not before time as the old loco was just about clapped out. Now the old girl is a museum piece at York. On this roistered working it was usual to have another engine for the "working" back to Bournemouth. On this occasion, the running foreman of Eastleigh sheds allocated us a D.15 Class 4-4-0. This pleased me, I liked to work on these powerful "Urie" rebuilds of "Drummonds" originals. Now it was tender first to Southampton Terminus to work the night mail ex-Waterloo to Weymouth. On this train it was a fast run to Central Station. On arrival there we were to be relieved by Dorchester men. I was now off to my bed.

DANGER FROM THE THID RAIL

During my time at Bournemouth depot the lines were steam south of Woking on the route to Waterloo, and Portscreek junction on the outskirts of Portsmouth when going south along the coast, did we meet the electrified third rail system. When at Three Bridges many lines were electrified with a 660 D.C. live third rail, so crews were in danger when climbing down from their engine to change the red tail lamp etc., they had literally to watch their step as many men have suffered from an electric shock or burns from touching the live rail, made worse as they usually be holding on to the cab steps hand rail, so making a path to earth. Working over roads with no live rail system, was no problem, but going into the live rail system again engine men had to be alert to the danger. As a signal lad at Keymer crossing on the Eastbourne line, I have seen dogs run down the track towards Spatham Lane, touch the live rail, receive a shock and bite the offending rail, sadly that would be its last bite.

BOURNEMOUTH WEST TO SALISBURY

Usually a 'T9' coupled on to four carriages, during the trip most of the fireman knew where most of the pretty young girls resided, and mild flirtations naturally took place on the local platforms. As young ladies travelled to work or college.

After passing through Downton tunnel we were the same height above sea level as the top of Salisbury Cathedral spire, which we could see in the distance, across the fields and water meadows. This train entered the busy east bay platform shared with the Eastleigh and slow Andover trains. On this section the fireman unlike the Brighton line was expected to do the uncoupling and rearrangement of head code lamps and route discs. This completed the coaches were shunted to release the engine which went off to the motive power shed and coaches were pushed back into the bay. At the sheds, a quick look at the fire bars for clinker, and c1eanout. Then on to the turntable, and what a table it was, once the locomotive was balanced and the locking lever catch released. The table could be pushed around with one hand, giving credence the tales of wind catching locomotives on turntables and spinning them. This must have been one of the Southern’s finest turn table perhaps it had roller bearings or the fitters kept it in good condition. It also had an operator in attendance to operate it. But guess what? Later this turntable was converted to vacuum working, which involved connecting the turntable to the steam engines vacuum system, which required a showing of at least 21 inches of vacuum the gauge. This made the engine men's work a lot easier, as by this time some turntables were in terrible condition. This did however mean the attendant was made redundant and properly ended up working on the ashpit or coal stage. Often these men started out as footplate personnel, but due to failure of the annual medical, were relegated to lesser duties. Although working on the railway was a job for life, it did not always mean promotion.

Now the engine re-joined the carriages for an easy return run back to Bournemouth West, with time to enjoy the scenery. Now the villages we passed through though once in Hampshire now come under Dorsetshire. And of course now the line is closed

SPAM CANS