1914

Submission of a new National Programme and revision of

Conciliation Scheme postponed owing to war situation

A up train coming of the Bognor Branch at Barnham Junction 1914

ACCIDENT AT WORK

16th February 1914

Coulsdon (?) Engine driver William Pogmore (aged 56), whilst oiling under his engine No.391 in Coulsdon locomotive shed. On the same shed road as engine driver F. Seeker and his engine No.379, when engine No.565 driven by engine driver J. Shaw collided with engine No.379, driving it forward into engine No.391, which moved one and half yards, driver Pogmore was caught between the driving rods. It was recommended that a more suitable place to be provided for engines to stand whilst enginemen are preparing them and men be adequately protected. The accommodation at Coulsdon locomotive depot in such that half of the locomotives may be placed in traffic sidings. No pits in the sidings, nor provisions for men's protection while they get their engines ready.

.

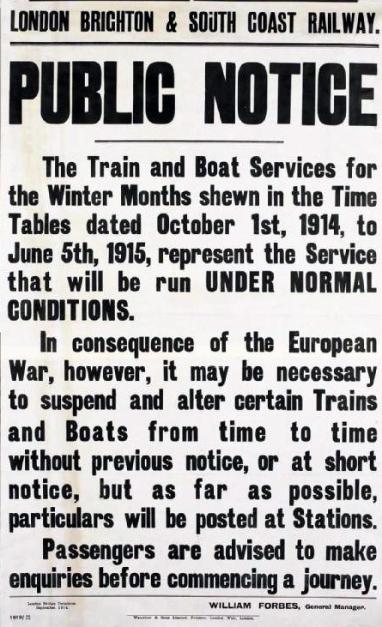

The First World War 1914 - 19

ACCIDENT AT WORK

30th March 1914

New Cross fireman Herbert W. Turner whilst New Cross locomotive yard was uncoupling wagons by hand, when the movement of one wagon caused his finger to be caught and crushed. The provision of shunting poles have now been provided. The practice of moving wagon using a towing chains should be abolished as soon as possible. The use of capstains is recommended. The breakages of chain and wagon side loops have been frequent.

New Cross shedman William Copeland was Turner's driver.

STORIES FROM THE SHOVEL

extracted from RTCS book on locomotives of the LBSCR

Whilst on shed duties at New Cross on the night of 17th May, 1914, Driver McKay failed to notice that his fireman had turned him into the wrong shed road. At the time, new inspection pits were being built, and in the darkness his engine "I1 Class" No. 33, crashed through the wooden protection barrier into the gaping hole. Much trouble was met re-railing this rather large tank engines in the confines of the shed.

ACCIDENT AT WORK

31st May 1914

Brighton engine driver Robert Cox (Injuries Multiple (aged 41), whilst shunting a loco was ahead of seven wagons and two of them were four feet apart, IM went into the gap and the loco closed up to the wagons and IM coupled them up. But a wagon derailed and IM was pinned by a wagon buffer and the other wagon's pillar. The derailment was caused by coal on the rails. But an attributed to IM disobeying working instructions by not using his shunter's pole or waiting until the wagons were buffered up and idle before coupling. The coal had fallen onto the line during coaling on the coal stage road where an accident took place.

The First World War 1914 - 19

In common with other British railways, the LB&SCR was brought under government control during the First World War. Until then it had carried relatively little heavy freight for much of its existence, but this situation changed dramatically at the outbreak of war. The railway was responsible for carrying the bulk of the stores and munitions delivered to the British troops on the continent, principally through its ports of Newhaven and (to a lesser degree) Littlehampton. This included nearly seven million tons of freight, including 2.7 million tons of explosives. It necessitated an additional 53,376 freight trains over the four years of the war, as well as an additional 27,366 troop trains.

This additional traffic required substantial improvements to the railway infrastructure,

notably at Newhaven harbour, where electric lighting was installed, but also at Three

Bridges, where a new freight marshalling yard was established, and at Gatwick and

Haywards Heath, where passing sidings were constructed so that the frequent passenger

trains would not be impeded by the slower-moving freight. Some munitions trains were routed to Newhaven via the Steyning Line to Brighton so as to avoid congesting that part of the Brighton main line which had only two tracks.

Prior to the First World War engine cleaners received no holidays. However, engine cleaners

who had worked as a fireman for at least 9 months out of the previous 12 months were

awarded 3 days annual holiday; but only approved fireman were able to meet to meet this

requirement and by the time they could fill 9 months of the year with firing turns they had

virtually ceased to be cleaners. Moreover, even those footplatemen who were entitled to a few days’ holiday were forbidden from taking it during the summer service.

Therefore some cleaners/fireman belonged to Territorial Army or to the Royal Navy Reserve.

This was not them being patriotic, but it was a way of getting paid holiday whilst attending

summer camp each year. But things caught up with them in August 1914 when the Great War broke out.

The Territorials and Reservists were mobilised almost immediately and caught up in the

patriotic fever which swept through the nation. Many others volunteered for active service.

By the end of August, Brighton had seen the departure of 25 enginemen;

18 cleaners,

3 approved firemen

4 firemen.

The exodus continued in September with another 16 departures;

8 cleaners,

5 approved firemen

3 firemen.

Five more volunteers went in October - November;

3 cleaners

2 firemen.

Thus in a very short time, Brighton had seen a total of

29 cleaners

8 approved firemen

9 firemen

all going off to fight for their country. This was approximately one in ten of the entire

footplate grade at Brighton.

Only 2 of the 46 loco-men did not return after the war was over. It is possible that most of

them served in the Railway Operating Division which had a causality rate much lower than

in the trenches.

This sudden depletion of loco staff raised concerns within the locomotive department and an

otice was duly issued by Lawson Billinton Locomotive Superintendent, stating that the

footplate staff could best serve their country by staying put and continuing in their normal

jobs. A lot of trains were going to be needed to supply the British forces in France and those

trains couldn’t run without engine crews. Indeed, from thenceforth any enginemen who

wanted to ‘join up’ for military service would first have to hand in their notice to the L.B.S.C.R.: in other words they would have to resign from their job on the railway.

Extracted and adapted from the book

Yesterdays Once More

by Fred Rich

DEATH IN SERVICE

24th November 1914

Brighton engine driver A.G. Pelling died in service on the 24th November 1914, aged 56. Joined the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants Brighton No.1, on the 27th October 1877

ACCIDENT AND DISABLEMENT

26th November 1914

New Cross No.1 engine driver A. Blackman old age 26th November 1914, aged 60. Joined the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, on the 15th October 1887

ACCIDENT AND DISABLEMENT

30th November 1914

Brighton No.2 engine driver J. Thompsett old age 30th November 1914, aged 60. Joined the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, on the 23rd August 1883

ACCIDENT AT WORK

2nd December 1914

Eastbourne (?) engine driver Walter Muzzle (aged 38), whilst working a light engine in Eastbourne. Whilst waiting for the signal to clear Muzzeell went to oil the crank shaft, when another engine propelling empty coaches collided with his engine injuring him. Porter P. Bourne admits he should have obtained permission from shunter Wade who was in charge of the movement. Wade could see Muzzell's engine. The responsibility for the accident rest on Porter Bourne.

ACCIDENT AND DISABLEMENT

31st December 1914

Eastbourne engine driver J. Clark old age 31st December 1914, aged 60. Joined the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, on the 17th September 1887