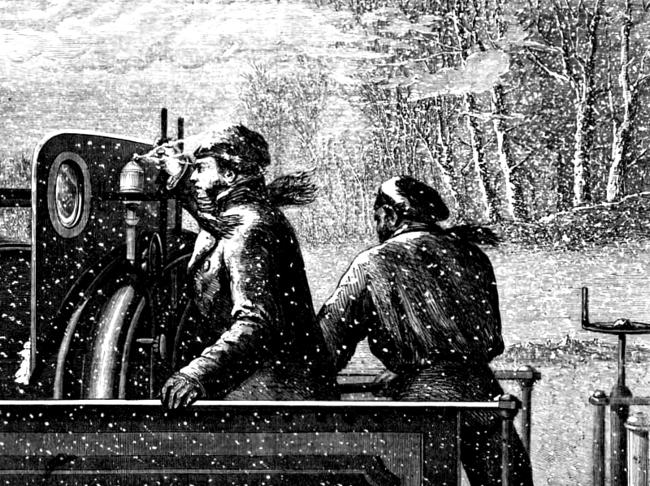

“On fire-horses and wind-horses we career,” says Thomas Carlyle, describing what De Quincey called the "glory of motion." We admire the mighty forces, fire-fed like Enceladus, but we forget the fine fellows who control them in sun-time and in snow-time. The man who guides, and the man who feeds with fuel of flame, the monster of Titanic birth, the Frankenstein monster, with muscles of steel and heart of fire, we regard as if they were mere abstractions, instead of men with emotions, and homes, and wives and children of their hopes and poverty. There are no more dauntless heroes in the world of work than engine-drivers and stokers. To drive an express through the black and bleak winter night, with unknown lurking calamity in the mysterious darkness in front, and with two or three hundred lives unconscious of danger behind, not once only, but night after night, as a daily routine of labour, is an exploit far worthier of reward and decoration than is commonly allotted to it. The sallow, earnest faced man on the engine, with keen, scrutinising eyes, wears no scarlet coat. His attire is greasy and grimy, and his appearance is unprepossessing. The only music with which he goes into action is he shriek of his engine; the shots he hears are the explosive reports of the fog signals sending up a shower of sparks under the grinding wheels, as the train burns its way through the pitchy gloom, and

Shears the moonlight with its shadowy shrouds,

Till every breath and pant

Mirrors and paints itself against the clouds,

Like northern lights aslant.

Illuminations the driver has, too, but they come to him a blaze of bewildering signals, green, white, red, each point of light hung up like stars in the sky, or lying amid points and crossings on the track, and revealing the cold network of steel, full of vital import. Bonfires he has, but they are kindled in the fire-box, and send out a strong white circle of intense light, in the darkness of a dark tunnel—a medallion in which the driver and his "mate" stand in Rembrandt relief from the shuddering background. These humble heroes of the engine footplate, obscure and unostentatious, are far greater men of distinction than we wot of. Their tragedies are silent; their triumphs occur day and night all the year long. Their campaign never ceases. What soldier's nerve is equal to the straining task of the driver looking out for the sudden signal, or the first symptoms of danger ahead, the face exposed to wind and wet flitting past in a million needle points, with the speed of a whirlwind, the lower part of the body burning from the heat of the molten furnace, while a flash of white and red determines the fate of a train and the destinies of the people behind that silent, sober, and dauntless driver.

They ride in cosy little cushioned rooms, with glass windows, rain-dotted with the tempest, and a cheerful gleam of light to grace the gloom. The man who has control of their fortunes is to them part of the steam which impels them from departing place to destination. They do not regard him as a brave-hearted human being. The porter who rolled their luggage along the platform, with a clumsy " By-yer-leaf," received his expected douceur; the guard behind, with his smart uniform and civil manners, received his “tip” in silver, and his attention deserved, perhaps, the compliment which the Prince of Wales at a recent banquet paid this obliging official. But the engine-driver is too oily and cokey, too rancid and rough, too much like the Toodles of Dickens’ story, to attract the traveller whose life is in his keeping.